3 Ways To Do Working-Class Foreign Policy

America can relate to the world in a way that benefits the common good. But how?

A lot of people are rightly anguished about Gaza, feeling helpless to stop Israeli war crimes, cyclical violence, and an expanding regional war. That desperation is what leads people to the streets, to build encampments, and at times to more extreme measures.

Yet, mass vocalization in the form of public protest is but a tactic, and foreign policy is heavily insulated from it. Worse, street-based demands—while righteous and necessary—are typically pinpointed. Some egregious thing happens in the world that must stop, and so the demand of the people is usually narrowly about that egregious thing.

Imagine if protestors got their way in 2003 and the US didn’t invade Iraq—that would’ve been a freaking miracle! Yet primacy would’ve still been US grand strategy. The Global War on Terror would’ve continued killing people and radicalizing suicide bombers all over the world. And brown people in America would’ve continued to be treated like second-class citizens, surveilled by the FBI, and put on terrorist watch lists. Accordingly, we would’ve still ended up with Trump and the fallen state of our current politics. Protest as a form is capable of targeting the events but not the systems that produce the events.

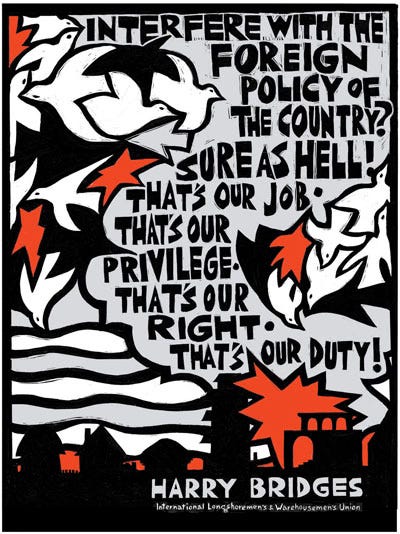

How, then, to think productively about relating to the world in a way that benefits the majority of Americans, which by definition would be a working-class foreign policy?

Any question about what internationalism should look like is also necessarily a question about foreign policy preferences. And so it would be useful to clarify that there are three different—sometimes complementary, sometimes competing—ways we can think about building a foreign policy for the working classes.