How I Almost Became a Palantir Democrat

First stop: San Francisco’s Embarcadero. The air was electric but I still needed Blue Bottle to wake up.

Waiting for my slow drip to finish, I eavesdropped on a hoodie-clad tech bro in front of me in the queue. He was explaining to another his app startup and how quickly they were burning through their “runway” before needing a Series B funding round. I salivated at the money sloshing around in the name of creation. It was, indirectly, what brought me to The City to begin with.

I was actively trying to land a gig in California, to permanently escape Washington, DC.

Armed with a cup of rocket fuel, I Uber’d over to the Presidio—a gorgeous former army post turned wooded area overlooking the Golden Gate Bridge. One of my besties ran the World Economic Forum’s new Silicon Valley office there. He had convinced John Kerry to open up a Silicon Valley presence for the State Department and nominated himself as the man on the ground, then left government but never left the Bay. I wanted to know how he did it.

Throughout 2015 and 2016, I was straddling the intersection of academia, think tanks, and the national security state. A freshly minted PhD, I was interviewing for tenure-track academic gigs and adjuncting at Hawai’i Pacific University. My day job, though, was at a Department of Defense War halfway house for defense intellectuals nestled in the Pacific—part think tank, part university, part military academy. I had intentionally fled Washington for Honolulu, but the Beltway was trying to pull me back in.

In April 2016, three different people approached me to join Hillary Clinton’s campaign as a foreign policy adviser (unpaid). The pitch from each was basically, “There is no alternative, and working on the campaign is your ticket to a political appointment.” Clinton was pursuing a monopoly strategy on foreign policy talent, trying to lock in anyone and everyone as part of her sprawling technocratic empire; if you were with her, it meant you couldn’t be against her. I thought Clinton was a terrible candidate but I seriously considered joining her team, as a hedge if nothing else. I really didn’t want to go back to Washington, but Honolulu felt unsustainable too.

As a location, Hawai’i suited me (and most people) much better than the Beltway. But the cost of living was absurd. The humidity was unceasing. And the pervasive Haole mid-century nostalgia culture that accompanied a local economy dominated by military Keynesianism and that rendered Kanaka Maoli into second-class citizens on land stolen from them…gross. In a different version of Hawai’i, it’s the only place I’d want to be. In this version of Hawai’i, I felt like I was living on Tatooine as an agent of the Galactic Empire.

I had also become too much of an independent mind for an institution of military education; anyone there would tell you I just didn’t fit. So I was looking for a way out of Honolulu that wouldn’t require returning to DC.

For a while, I thought Silicon Valley might be my third way.

Some of my friends from Obama’s Pentagon trekked out West, and I was jealous that they lived in a temperate climate; wore hoodies to work; and ate Mexi-Cali food anytime they felt like it. Lifestyle aside, they were also pioneers rekindling a strategic relationship between Big Tech and the national security state—a project I supported at the time. One worked on policy for Twitter now; another for Google. One was helping Uber destroy the taxi unions across East Asia. One was somehow at a VC, despite having no background in tech or finance. Two others were at Facebook doing god knows what. But at least three (maybe even five?) ended up at Palantir, in senior roles no less.

I honestly couldn’t make heads or tails of what any of these policy-tech pioneers were doing. But I needed to find out in order to judge whether California could be my neither-Honolulu-nor-Washington. So I’d set up a series of meetings around The City to catch up with as many friends as I could.

My time in the Pentagon convinced me that “the future of war” required spinning technology from the private sector into the hands of the national security state—a reversal of the military acquisition paradigm up to that point. And I knew that everyone who ventured West shared this belief that “spinning in” commercial innovation was the only hope for sustaining US dominance.

I had not yet lost my religion—military primacy and American exceptionalism. I also hadn’t thought through all the implications that followed from collusion between Silicon Valley and the national security state. I knew it presupposed social ties between tech and foreign policy—a scheme I wanted to capitalize on.

Yet it also meant massive, unending wealth transfers from taxpayers to Big Tech companies to make them into military contractors. This project meant the tech economy would fuse with the permanent war economy. Military-industrial largesse, in turn, would allow American oligarchy to sustain itself without ceding anything to the working class; a way to buoy “national” economic growth despite growing unemployment and inequality. A permanent war economy meant permanent economic insecurity for even skilled workers. Worst of all, there was no way to expect democracy or anything resembling peace to survive if this project succeeded.

But I wasn’t thinking about any of that. I had never even heard of the permanent war economy. I was just trying to be a Californian again and get out of this career bind.

My buddy at Presidio offered a walk-and talk, taking me around the campus—a giant, multi-purpose national park—before bringing me up to his office. He laid out for me a version of what I heard in ten different conversations that week: He knew someone at the World Economic Forum from government meetings with such and such while he worked at the State Department. Over drinks and dinner, he pitched that person on the value he could bring, much of which had to do with making connections to Stanford and the DC policy world. A simple recipe, but an impossible one to replicate.

More than one of my friends advised that Palantir was my most-likely route to the West Coast. The firm had a couple job openings at the time, but it would’ve been a devil’s bargain. The descriptions read like traditional military contractor jobs doing data analysis for opaque purposes; the kind of soul-sucking work that alienated me from government in the first place. Did I care more about where I lived, or the kind of work I did?

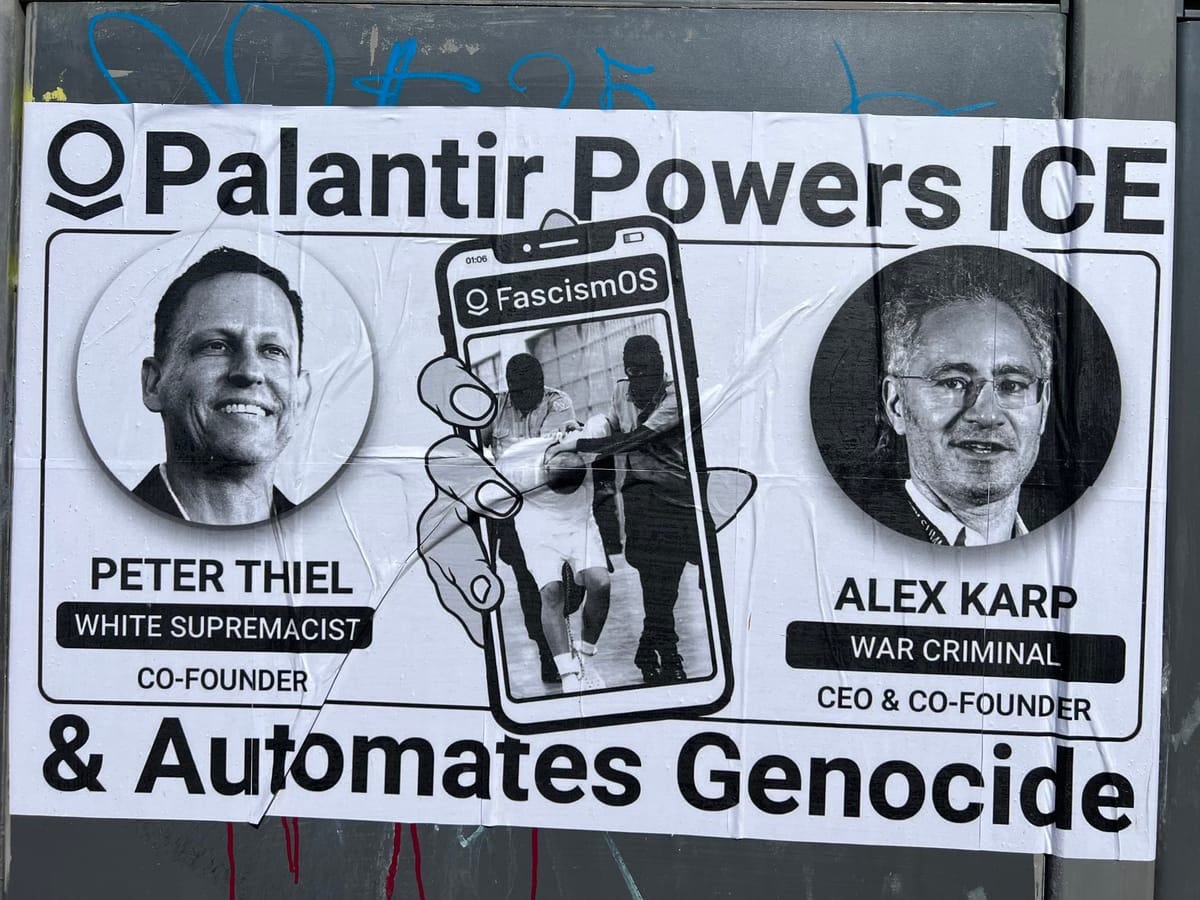

In 2016, Palantir did not yet have a reputation for drug-addled war crimes and Islamophobia, but neither was it viewed benignly. There was also no veil of deniability with Palantir. Notwithstanding the location, the vibe was that you were part of the national security state, not Silicon Valley per se. And during this trip, I just happened to be reading Dave Eggers’ The Circle, about the thinly fictionalized dystopian world created by idealistic data analytics and surveillance tech—precisely Palantir’s specialty.

It all added up to hesitation for my part. I still found something about the Bay Area intoxicating, but I was being nudged in the other direction. My wife, who went to Stanford and worked there for a few years, had a hunch I’d hate the tech-bro culture even more than having to align my politics with the interests of billionaires. She knew the place, and she knew me.

There was also another source of growing skepticism that was more meta, if you will. The kind of work my friends were doing seemed devoid of purpose; at best just mind-numbingly boring. Do I really want to be an agent of deregulation in East Asia? Could I be happy if my life’s work amounted to making billionaires richer?

Contrary to what I had assumed, jobs weren’t just falling from trees; if I wanted to make the move, I’d probably have to start out as a de facto military contractor at Palantir and then look to move to a startup or one of the FANGs (Facebook, Apple, Netflix, Google).

I walked away from that trip unsure about my Silicon Valley prospects, but also about whether I really wanted to be there after all. I considered reaching out to my Palantir people but never pulled the trigger. I kept up the Silicon Valley job search a bit longer, and kept the Palantir option warming on the stove too. But I ended up not needing to apply to any positions at Palantir because I won the Ivory Tower lottery.

As a Hail Mary, I had spent the entire year applying for academic jobs. Teaching and writing were the only things I actually enjoyed doing anyway (other than jiu jitsu). When Clinton lost in November 2016, I was in the middle of four different university interview processes. Victoria University of Wellington came through with an offer for a New Zealand adventure at a perfect time.

Much about me has changed in the past decade, which has zoomed by. It had been a while since I thought about my 2016 soak-and-poke in Silicon Valley, but it all came rushing back a few days ago. A friend sent me an op-ed in the Washington Post by someone I worked with in the Pentagon. Until recently, she was a senior executive at Palantir. Her arguments were logical extensions of the way I had once thought about American power and Big Tech; arguments I’d have made if I ended up in Palo Alto. They were also appallingly out of step with any claim to peace, democracy, or equality.

The take in her op-ed amounted to advocating for tech monopolies, vilifying Lina Khan, and urging US taxpayers to transfer a further $50 billion of society’s wealth to make a slush fund that would subsidize Silicon Valley on top of the already trillion-dollar war machine. I’m not even exaggerating. The kicker was that the point of the piece was to urge the Democratic Party to embrace companies like Palantir—to stop worrying and learn to love the death-tech industry, lest they fund Republicans.

There was an irony in her Jeff Bezos-approved pitch: The CEO of Palantir had been a Democrat; Palantir’s bottom line had flourished during the Biden administration; Palantir’s senior leaders counted among their ranks several Obama-era policy officials; and Palantir even contributed to the electoral campaigns of Democratic politicians. In being the party of the national security state, the Democratic Party was also the party of Palantir. The op-ed was pushing on an open door.

I came to see all this with critical distance only because I first came to see a long unacknowledged contradiction at the heart of what my politics had been.

On the one hand, I had always found the idea of profiteering off the permanent war economy deeply unappealing; one of the reasons I’d fled DC in the first place. On the other hand, I had believed that global stability depended on America hoarding the greatest share of world power—an imbalance that I imagined being a global public good.

Washington has a way of seducing you into confusing power with virtue. And it was not only my ignorance of political economy but also my unquestioned belief in American power—the power to bomb, to commit war crimes, to flout international law—that made me think the militarization of Silicon Valley would be virtuous enough to be worth my labor.

Hey, there! You might have noticed that I’m offering more of Un-Diplomatic without the paywall; I’m trying to keep as much as possible public. But to do that requires your help because Un-Diplomatic is entirely reader-supported. As we experiment with keeping our content paywall-free, please consider the less than $2 per week it takes to keep this critical analysis going.

Van, your hesitation around Palantir reads less as uncertainty than as an early instinct. Even before the fusion of Silicon Valley and the national security state fully came into view, the bargain itself felt too Faustian to sit comfortably, at a moment when you were still testing whether distance from Washington might also loosen its hold on how power thinks. Wellington offered something quieter. It became an antipodal vantage, distant from the geography of power yet still within its telemetry. From there, the line Machiavelli draws between virtue and virtù comes into focus. What emerges is the recognition that technical brilliance and institutional momentum can drift away from moral purpose. Remaining apart, in that sense, from political propinquity and groupthink: a position that allows reality to register more objectively than consensus ever could and that is why your voice carries weight.

Van— I loved this, and so much appreciated hearing about your struggle, as not long ago I'd read a fine take-down of Palantir in the NYReview of Books and so was prepared to hear about your much earlier awakening. What I hope to hear you talk more about is something even more basic, even existential: your coming to value "peace, democracy, and equality"— how those values became instilled in you (as they clearly have been), and how they can be realized in a post "rules-based" social and political order, now, today. Not that they were realized pre-Trump! In a world of flux and Palantir dominance, where can we find solid ground for the values you (and I) cherish?