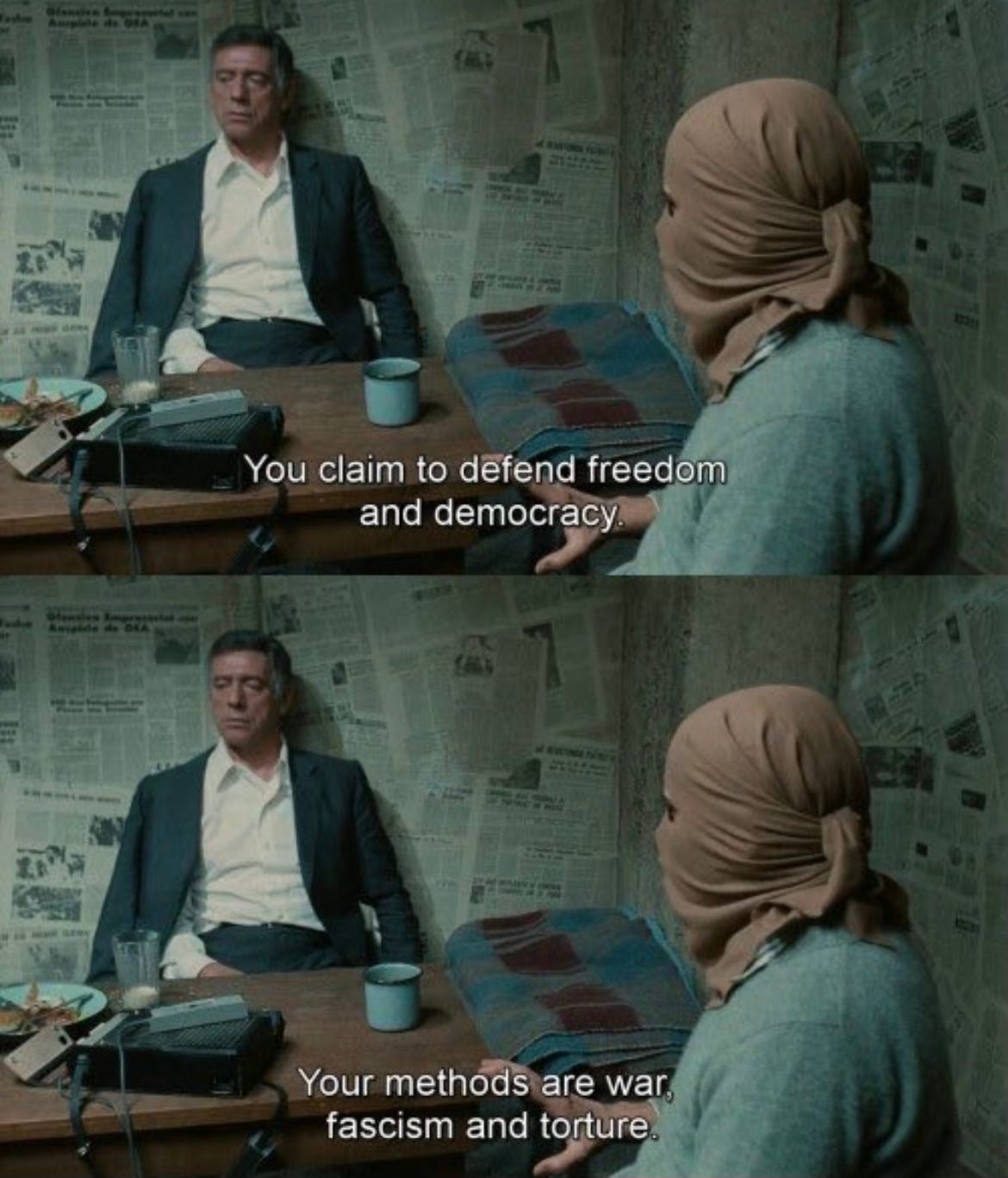

Who Benefits From Political Violence?

Part of a course I teach on strategic studies covers “strategy from below.” The subject of strategic studies has a very strong bias toward states and nations. Accordingly, most of the literature focuses on the strategies of military force that states pursue.

I find this a bizarrely narrow scope, so I have students als…