3 Truths About the Democratic National Convention and Foreign Policy

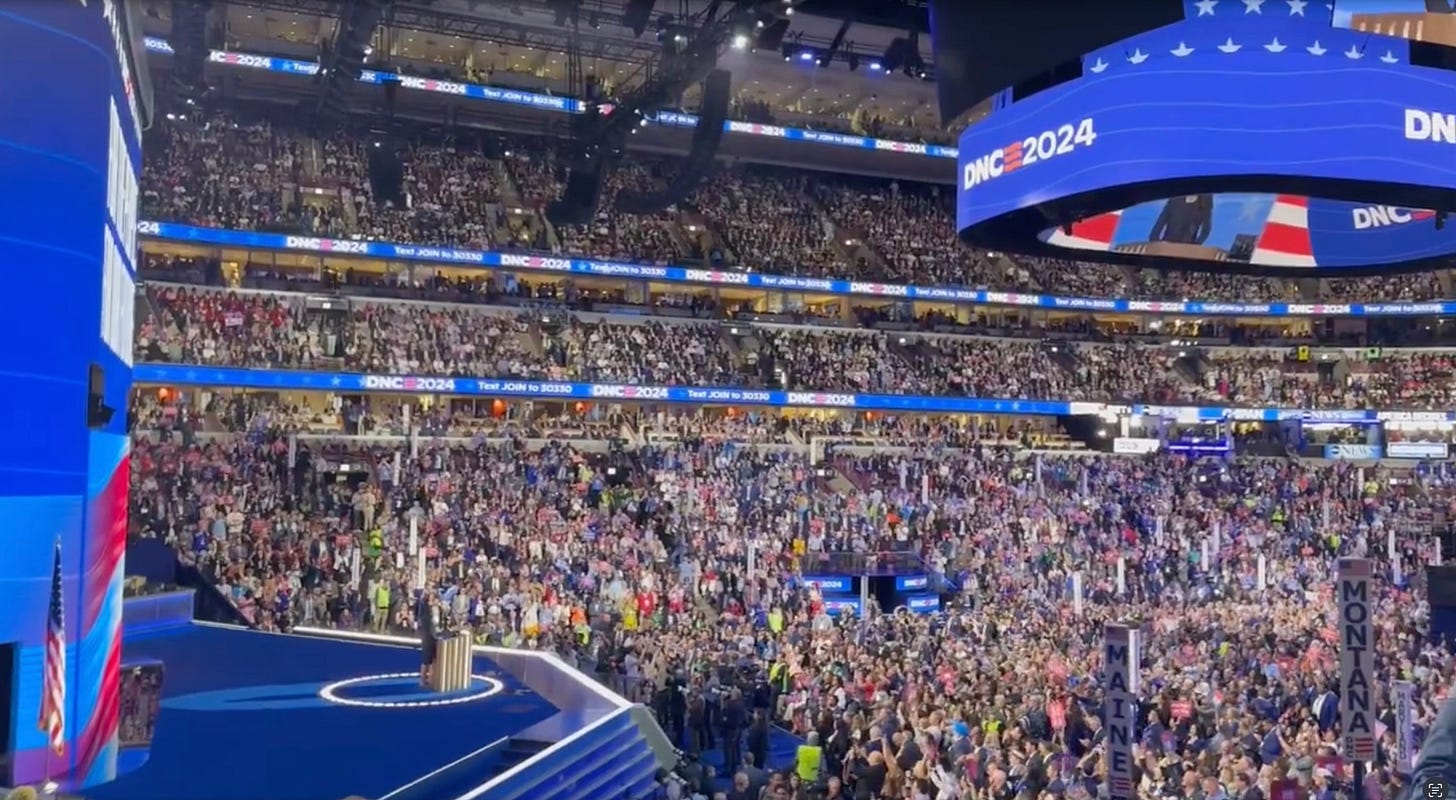

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is in full force and the vibes are strong. It’s awesome seeing a massive multiracial crowd of folks experiencing joy, dropping hip-hop references, and getting caught up in labor revivalism. In moments like these, being in New Zealand gives me serious FOMO.

But it also affords me perspective, which those caught up in the tide must struggle with.

Anand Giridharadas, author of The.Ink, had a stimulating post about the festivities—so stimulating that it scored him an appearance on Morning Joe to talk about it.1 He says that there’s been an internal war between two types of leadership in the Democratic Party. In the piece, he suggests that, amid the coronation of Kamala Harris and Tim Walz, a new cadre and approach is emerging that he calls the “Brat Pack.”2

The old type was defined by:

sobriety, risk aversion, a focus on doing the work rather than talking about it, staying high-minded, and refusing to compete for attention with a carnival barker.

The other, new type—the “Brat pack”—he says, is defined by:

risk-taking, storytelling as a paramount goal, speaking to emotion, making people feel things and want to sing from the rooftops, grabbing and holding attention. In recent years, the former camp has been firmly in command.

Insofar as Anand is correct, it signals a new era of politics and I think that’s what I like about his take.

There’s a political scientist, Ron Krebs, who wrote a book in 2015 about what he called “national security narratives.” In it, he made the case that, during settled narrative moments, where there’s a broad consensus in the national narrative, politicians will be most successful asserting technocratic, policy-heavy arguments. In moments of unsettled narrative, Clinton-esque arguments are losers and story telling is the way to win.

What I loved about Krebs’s argument is that it was (perhaps inadvertently) an exercise in conjunctural thinking. I’ve been doing this in some of my work too, but the idea is that you have to match your strategic mode to the moment in which you exist. As obvious as that seems, few seem to do it, and nobody really theorizes that way beyond loose citations of what Gramsci and Stuart Hall had to say.3

Anand is gesturing at this sort of thing—ie, at the shape of our conjuncture and what it will take to win elections in it. If Anand’s right, it will be consequential because the Brat pack gives up on the myth of the median voter. That would be a massive mental shift for political consultants and pollsters. You’d think I’d be all about that! Aspirationally, I am.

But this whole “Brat pack” thing is overstated—do you mean to tell me that previous-era politicians weren’t trying to make emotional appeals? It’s not really based on evidence. It also seems to conflate political style with political vision. Obviously how you market yourself in politics matters, but it’s the mistake of an entire generation of Democratic leadership to think they could substitute aesthetics for a meaningful theory of change. “Just say different words and we’ll win!”

Anyway, I’m of two minds about the DNC right now.

On the one hand, there’s a lot of positive energy in the left-liberal coalition and I want to ride that vibe to November. It’s tactically important. On the other hand, 95% of the evidence I’ve seen about Kamala’s foreign policy suggests it’s going to be like Biden’s or worse. I’m trying like hell to be hopeful, but if I’m right, then not only are a lot of people going to die while the economy curdles; it’s going to pave the way to MAGA victory sooner or later.

Regardless, I’ve gone through the DNC platform with a fine-tooth comb—especially its foreign policy section—and it’s mostly good on domestic policy and mostly depressing on foreign policy. At this point all I can do is tactfully call it like I see it.