Are Working-Class Interests Progressive?

A properly progressive foreign policy1 is a working-class foreign policy. The complication is that working-class demands on foreign policy are capable of breaking in radically different political directions.

Let me back up a second.

When I think about international relations, and especially when I critique US foreign policy, my perspective is oriented toward the material interests of the working classes.

But when I was writing Grand Strategies of the Left—a project that maps out different models of root-cause thinking about how the state should relate to the world—I ran into a troubling realization. The class position of those advocating for worker interests were inescapably bourgeois, even elite. Chris Rock’s joke hit a little close to home:

I’m rich. But I identify as poor. My pronoun is “broke.”

I kid. But seriously, missing in action from the public conversation about foreign policy while I was writing that book were the voices of organizations whose members actually were working class—specifically labor unions. They were part of politics during the Trump years, but they just weren’t pushing many foreign-policy demands at the time. Specifically, they were not offering positions on the list of issues that policymakers obsess about.2

And this is why I love one of the more recent trends captured in a short, punchy piece in The Nation by my friend Spencer Ackerman.

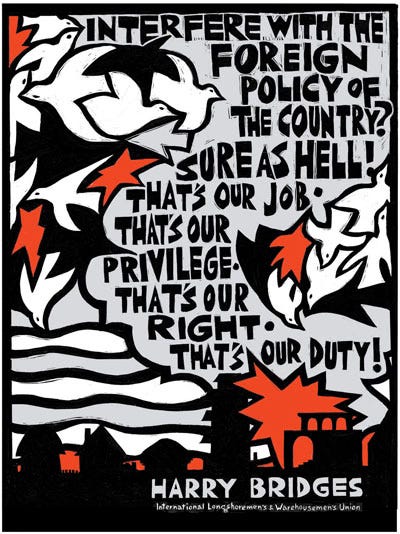

His column this week, “A Working-Class Foreign Policy is Coming,” foregrounds working-class voices speaking directly about foreign policy interests via their unions.

As Spencer tracks in his piece (and as Alex Press has tracked for a while), dozens of unions—including the mighty UAW—signed onto a statement demanding an immediate ceasefire and an end to Israel’s terror campaign in Gaza. That’s the same position that progressive, social democratic, and antiwar voices have advocated from the start.

And whereas the UAW is actively investigating how to rekindle the peace-conversion projects from the ‘90s and divest from the military-industrial complex generally:

few in respectable foreign-policy circles consider the size of the US defense industry a problem to be solved. That’s a measure of how underrepresented the working class is in US foreign policy.

I’ve said this many times in many settings, but the thing that alienated me from the Washington Establishment was precisely its cold shoulder toward the working classes. In the preface to my damn book, I even bemoan:

why is the plight of workers—average Americans—totally absent from the geopolitical machinations of the national security state?