How I Write

I’m making this post available to all to ring in the new year, but if you have some spare change in the sofa and appreciate my work, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription!

When it comes to writing, I’m a volume puncher.

I’m also acutely aware that there are folks out there who write even more than I do. But I write more than most. Depending on your disposition, that could be either enviable or really annoying.

Regardless, one of my pet interests is writing as a craft. I love finding out how other people go about doing this incredibly hard thing that pays less than working at Starbucks. And if I’m keen to read how other people do it, it strikes me that other people might be of a similar mind about how I do it.

So here’s the n=1 case study of how I work. I hope you can take something from it. If you’re so inclined, feel free to share your process!

Writing As Habit, Writing As Lifestyle

I put in my 10,000 hours.

When I was eight or nine years old, I would use a typewriter (!) to write out the dialog from Eddie Murphy skits on Saturday Night Live (reruns). English was one of the only subjects in school that I found stimulating. And in high school, I wrote a conspiracy-theory filled screed (manifesto?) that extended for over a hundred pages. It was nonsense, but also a lot of work, and my way of trying to make sense of the world.

When I was in the military, I wrote constantly because I went to school at night. But I was also one of those dudes who kept a diary, which got me in the habit of regularly putting thoughts on paper.

Grad-school writing made me realize that I wasn’t actually sure what I thought until I committed pen to paper. I often have a gut reaction or impulse to take up a particular argument, but then as I work out my defense of that position via the written word, what I think ends up changing dramatically.

My lifetime of writing set me up to be one of the more prominent public scribes in 2017 and 2018, when Trump was threatening nuclear war with North Korea.

Like Anna Fifield, Jeffrey Lewis, Ankit Panda, and John Delury during that time, I was writing my ass off, largely in service of warning the public about the nuclear dangers we were facing. All of us got a taste of fame then, but also a lot of nights with very little sleep because we were writing to the beat of a crisis that stretched on for quite a while (and then doing next-day media).

Cambridge University Press saw some of my public scribbles about the crisis and approached me to do a book—their first foray into the trade press world. They wanted me to write about the North Korean nuclear crisis in real time. Ankit and Anna also got similar (but better paying) books deals with other publishers. The challenge Cambridge set down for me was to do the whole project in six months. I accepted.

As added sadism, I arranged to publicly blog about my writing process every day in parallel with actually writing the book. I thought it would help publicity, but also help fuse my reading, thinking, and writing so that they would be inseparable.

Here’s me on vacation while writing that book (or at least trying to) in 2018:

Remarkably, that project succeeded well beyond my expectations, though by the time the book came out, the world had moved on from caring about North Korea.

But that project put an impossible standard in my head of writing books soup-to-nuts in six months. I haven’t pulled that off since, and probably never will again. But the process ingrained in me the need to be continually writing, literally every day no matter what else is going on. Even if only for 30 minutes.

Part of this is selfish—nothing beats the high you get from publishing a book. But the need to write is a torturous affliction, something that you power through because you can’t imagine not doing it.

When I started writing for Duck of Minerva in 2021, it was primarily because I needed a space to think, and I missed keeping my daily record of personal thoughts in parallel with larger book projects. And when I started this very newsletter the following year, it was an outlet for candor that falls outside the international-relations remit of the Duck.

This newsletter and the Duck have become integral to my writing process. Basically, I’m still journaling, but now it’s with the knowledge that people will read it (yes, that distorts the final product).

Writing with Purpose

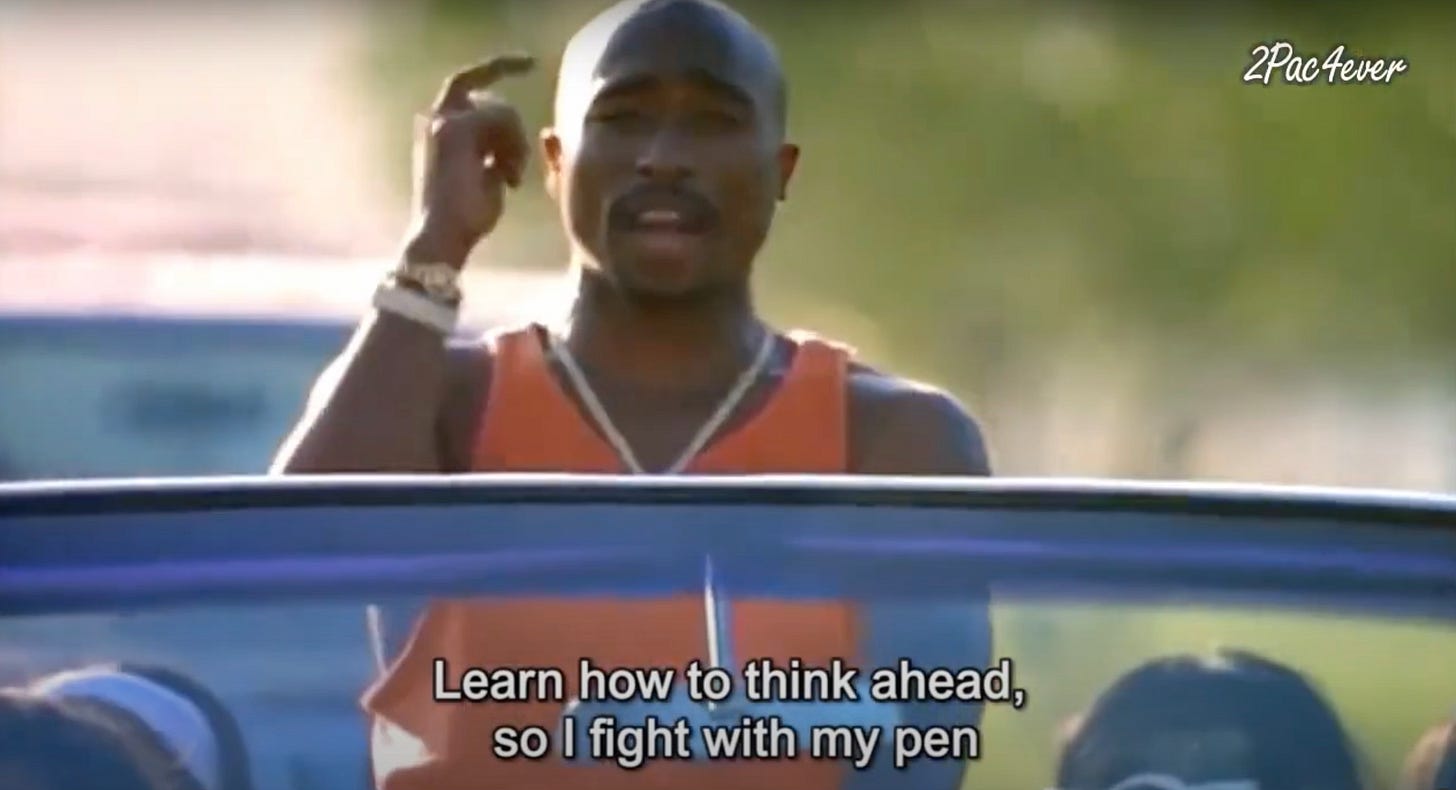

Like Tupac said, “Learned how to think ahead, so I fight with my pen.”

Writing is self-expression, but for me it’s also battling on a higher plane of existence; a more strategic means of fighting for a better world. I know that sounds grandiose, but it is what it is. As such, I write with a sense of urgency. I don’t just write to write—if you take the time to read my shit, I’m not going to bullshit you. And I’ve learned the hard way to be careful about writing on commission.

So when you see me bouncing from the Pacific to China to North Korea to US grand strategy to democratic socialism to labor politics to political economy to military strategy to IR theory and back…these are all areas of organic interest for me. I’m an inquisitive person.

I find something important that draws me to a topic—>I obsessively learn as much as I can about it—>and as I learn I also write, pushing forward corrections where I think others are wrong, filling the gaps I see in the “marketplace of ideas,” and saying what I think urgently needs to be said.

Sometimes this process leads to making enemies with people in positions of power, or gatekeepers of particular fields. The fire in the belly might force me to cross swords with people I’d just assume curry favor with, but without that fire, I couldn’t write like I do.

Also, let’s be honest—a lot of people who write about foreign policy simply do not know what the hell they’re talking about. They’re peddlers of conventional wisdom, nothing more. Somebody has to check these fools.

Writing Process

Before I lay out my writing method, it’s important to acknowledge that I enjoy certain advantages as a writer that you might lack:

My vocation allows me to write without it being my primary source of income.1

As a scholar, most of my time is unstructured. I’m accountable for A LOT outside academia—you’d do a spit-take if you knew all the non-writing balls I’m trying to juggle—but I’m usually free to organize my calendar in whatever way I see fit. And that means I can carve out writing windows.

My wife works full-time, but is very supportive of my writing when I have deadlines. Single parents have it really rough.

Through dumb luck and a powerful social network, I had media outlets willing to publish me from the jump. Having confidence that what you write won’t be desk-rejected by everyone affects productivity (FWIW, I do get a lot of desk rejections—I got two just within a week of Christmas).

I live in New Zealand! Pros and cons, frankly, but one of the pros is that I’m physically isolated from a lot of the distracting meetings and conferences that would occupy my time (and blunt my critical thinking) had I stayed in DC.

New Zealand’s professional class shuts down for most of December and January (it’s our summer and Christmas break all combined into a giant orgy of leisure). That’s a huge amount of calendar space each year to tackle big writing projects.

Ok, that was a lot of throat-clearing if you’re only reading this for the mechanical bits, but those meta aspects have a lot to do with my ability to write like I do, as much as I do.

Process-wise, I do write daily, but I have days that are generative and days where I’m unable to do more than just nip and tuck, pushing words around on the page. It’s important to understand that there are times when the words don’t pour out and that’s ok.

But I have certain practices that facilitate my writing even when I’m not in a generative headspace.

Working Bibliographies

I keep a handful of thematic MS Word documents with links to relevant literature and news articles. I read probably hundreds of newsletters, magazines, and newspapers, but I deal with that not by reading everything, but rather by scanning through what they send me and binning it in the right Bibliography document (or just deleting it).

So I have separate Bibliography docs on the Pacific Islands, Korea, China-Taiwan, debates within socialism, labor strategy, neoliberalism, defense strategy, MAGA foreign policy, nukes, and a few others.

When I start a big writing project (a book or journal article) that touches on one of these topics, I’ve basically got a massive head start on the research and literature review process. I don’t have to waste a bunch of time searching around—I just open up the relevant file.

I know people use apps to organize bookmark links and such, but I find that physically copying and pasting links and writing short-capture summaries of the link makes it easier to recall the resource when I start writing on the topic.

Active Reading, Stacking Ammo

As I’m reading a journal article or a book or whatever, I write down useful quotes and summaries of arguments. Sometimes I include them in the Bibliography docs, and sometimes I give them their own doc.

But the point is that my reading is an active process where I have my computer open and a pen in my hand. As I’m parsing through something, I’m pulling out quotes that might be useful and writing paragraph summaries of what I’m reading.

Stacking ammo in this way allows you to write without needing any creativity or associational thinking. You can be kind of robotic about it but still get down a lot of words. The result of stacking ammo while I read is that I have many building blocks—sometimes one or two paragraphs of prose for reach resource. I can then move those building blocks around and incorporate them into my writing during moments when the juices are flowing.

Many Doors Ajar

I probably have 80 placeholders for writing projects that I’ve started, but when I open the file, it could have nothing more in it than a working title and a couple turns of phrase that I liked. Anytime I get an idea for a writing project, I open up a new file and start writing down the argument and a few different versions of a working title.

If I’m really inspired by some new idea, I’ll put extra time into developing it but then eventually leave it for another day. Sometimes I don’t return to it for months, or ever. So at any given time, I’m “working on” four or five books, but really I’m only making progress on—at most—one at a time.

I do the same thing for this newsletter. I scan Twitter and BlueSky, find really bad hot takes, pull down links to interesting articles, and formulate some provisional ideas for posts. I’ve got close to 30 newsletter posts that I’ve started but not completed (for example, I started the recent piece on the Competition Metaphor in IR six months ago, but couldn’t manage to finish it until I saw a really shitty hot take from a neocon on Twitter and decided to punch back).

Routine Stuff

Finally, there’s a lot of lifestyle structuring that helps with my writing process.

I make my home office a semi-sacred space with a candle and hip-hop instrumentals—triggers that help put me in the zone when it’s writing time. Josh Waitzkin’s Art of Learning gave me the idea to build triggers into my practice.

I do 80% of my writing before 10am, and I try not to eat anything before 11am.

I limit my travel—it takes a toll on your body and your critical thinking abilities.

I’m in bed by 10pm most nights. It’s only possible because of working out.

I no longer chase research grants. Grant applications are in themselves a full-time job for scholars and think tankers. If money comes, great. But once Covid hit, I decided it was better to tailor my research priorities in ways that would not depend on external funding.

I don’t watch TV except during a window between 8-10pm each night. And for at least part of that I’m also usually fiddling around with one writing project or another.

I break all of the above routines sometimes. When I do, I try not to feel bad about it. Moderation in all things…even moderation.

So that’s basically it. No magic, but a lot of time spent with the craft.

And, if I can end on a note of exhaustion, I can’t keep writing like this forever. Two books in 2023 was an anomaly, not a standard. And while I have still another book coming soon-ish with Mike Brenes—it’s going to be big—I’m hoping to take my time with the one after that. Can the volume puncher become the sniper? 🤔

If you appreciate what I do, a paid subscription to this newsletter is a big deal. Aside from the access privileges you get, I have plans for the day I hit a critical mass of paid subscribers, and in the meantime, I use most of what I earn here to support other creatives and causes that matter to me.

Does "pushing words around" ever involve reading drafts aloud? I find it helpful for improving flow and reducing sentence length, but not very time efficient

We use the same method! Big topics in folders, and inside of each one several Word docs with subtopics, full with notes, quotes, links, etc. (many with your name on it, by the way), that then it is a matter to connect smoothly into a meaningful story.