Michael Anton is No George Kennan

The State Department’s head strategist is attracting comparisons that are both unearned and, if you know Kennan well enough, unflattering.

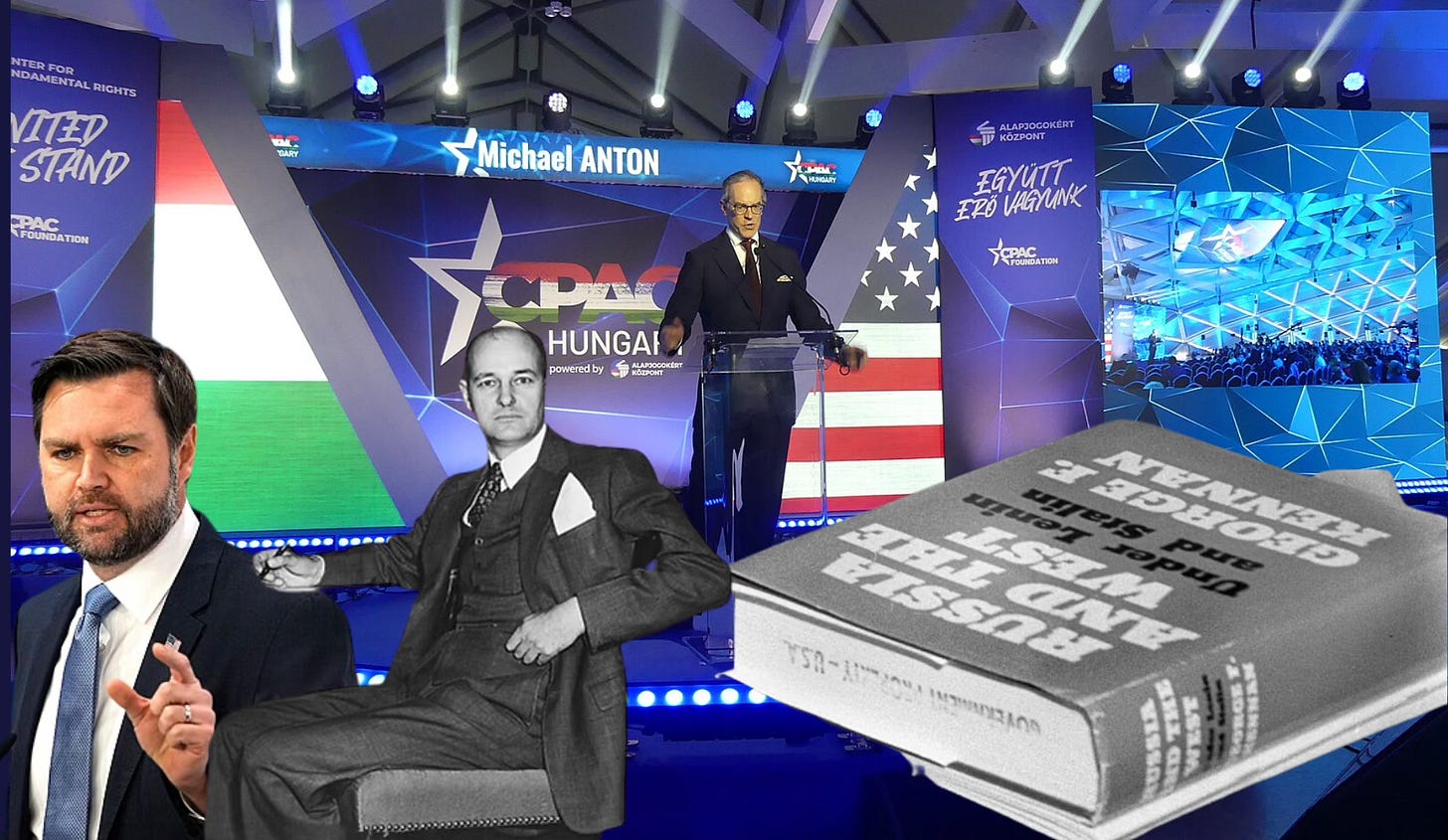

One of the most high-profile figures to enter the Trump administration has been conspicuously absent from the public spotlight: Michael Anton. Maybe I missed it, but I haven’t seen him give any interviews, offer any public commentary, or even make any appearances in his official role as Director of Policy Planning in Marco Rubio’s State Department.

Who is Anton? To say he is either a conservative or an intellectual misleads more than it reveals. He is, in a sense, both. But from what I’ve read of him since his infamous “Flight 93” essay in 2016, he’s a reactionary of a very discomfiting sort.

He seeks to build a monarchically-led nationalist political order at home—within US borders—that does not exist. Such domestic worldmaking is far from a conservative project in the Burkean sense. The MAGA and national conservative (NatCon) intellectuals style themselves as Leninist vanguards of a counter-revolution. Anton appears to be one of their leading voices. He even signed the NatCon statement of principles that purports to govern the country according to a renewed (far) right-wing ideology.1

Anton’s associations—with The Federalist, Claremont Institute, Hillsdale College, and of course Trump 1.0—are profoundly troubling. And I find some of the specific ideas he has about how political life in America ought to work terrifying, bizarre, and based on bad assumptions.

But from what I’ve read of Anton, he strikes me as the brightest bulb in a revoltingly unappealing flower bed. He’s probably the only MAGA/NatCon/new right intellectual I’m actually curious to have a conversation with. Not that it would go anywhere or lead to any changing of minds, but with him there’s at least a possibility of clarifying precisely where our irreducible differences lie. That’s not nothing.

So when I saw a NatCon publication, The American Conservative, run a piece flatteringly comparing Anton to George Kennan—author of the famed X telegram, brainchild of what would become a strategy of containment, and member of the noted “Wise Men” club—I took notice. Critical notice.

The thing is, I’m no great admirer of Kennan. He was not a good social fit for the WASP-y ruling class of his day, but he was part of it all the same. He had a very racialized worldview (in keeping with the times), and his preferences in geopolitics bore that out. Despite getting some things right—especially opposition to the Vietnam War and later-in-life criticism of nuclear policy—Kennan was, in the main, a political reactionary who thought democracy only suited certain people.

While it wouldn’t be fair to judge Kennan by the standards of today, these are sufficient reasons for me to not revere him as a totem of genius. He was a somewhat maladjusted product of his environment, and that environment is one that I (and many others) find problematic. As Jonathan Kirshner told me, and I’m paraphrasing, “to read Kennan is to slowly fall out of love with him.” I also got that impression from reading Paul Heer, who wrote a penetrating book about Kennan’s views on Asia.