My Hip-Hop Conscience

The first sign Washington, DC might not be the place for me appeared in 2009.

I had just started working at the Pentagon, and I was walking down its outer corridor with a new Obama political appointee. The hallways are insanely long, so we had plenty of time to chat. I asked him if he listened to hip-hop, just to make conversation. He replied, “I don’t really like music.” Stopped me cold. I’d never heard anyone say that before.

I feel awkward quoting Shakespeare because I’m not that guy, but there’s a line in Merchant of Venice that stuck with me more than anything from Romeo & Juliet or Hamlet or most other leather-bound classics:

The man that hath no music in himself, Nor is not moved with concord of sweet sounds, Is fit for treasons, stratagems, and spoils; The motions of his spirit are dull as night, And his affections dark as Erebus. Let no such man be trusted. Mark the music.

The man had bars!

My genre is hip-hop. If you’re from a different generation, or a different social context, maybe yours is something else. Or everything else; the kids seem open to all genres now. But if you “don’t like music,” there’s a good chance your soul is underdeveloped. Nothing captures the emotional vibrations of humanity better than song, and what is politics without emotion?

Many people in Washington love music. There’s a famous scene in In The Loop that even satirizes the contradiction of the Hill staffer who writes sanctions legislation by day and head-bangs to death metal by night (a scene that literally owes to my friend Spencer Ackerman, we talk about it here). But DC is the first place I’d ever been where I routinely met men who don’t care for music. Let no such man be trusted.

Hip-hop is ultimately a (deliciously rhythmic) form of expression, and that means it contains multitudes. It amplifies gaudy, self-indulgent, gold-encrusted excesses. It’s the soundtrack to those moments when we want to lose ourselves in party and bullshit. It can even be co-opted and used for pacification by those with power.

But hip-hop is also our conscience. When George Floyd’s murder went viral in 2020, I had trouble sleeping or eating for a solid week. I couldn’t even write; try as I might, the words just wouldn’t come.

Witnessing any murder is affecting, but it had outsized significance because of what it represented—an everything, everywhere, all at once moment. It flooded me with a lifetime of accumulated hip-hop tales of precisely the brutality I saw—a cop slowly murdering a man crying out for his mother. Pure domination. Hip-hop didn’t just tell me about the pervasiveness of this one incident that happened to be caught on camera; it diagnosed it as a problem of racial capitalism, the police state, and the violence baked into American culture.1 Even as I write these words right now, I feel a boiling rage that I can’t separate from my political commitments or analysis.

And that’s something else hip-hop is good for—the rhythm of boiling rage. The beat of radical change. Hip-hop has an excess of chest-swelling misogyny and machismo. The death promise it carries used to at once scare and entice me. But I’ve come to see the gangster’s almost reckless willingness to kill and die (lionized in so many lyrics) as something dialectically profound—a Fanon-esque necessity for moments when force and fear can be the only answer.

Hip-hop taught a generation of us to stand ten toes down when it matters. Zohran Mamdani exhibits the best of what that can look like, and it should be lost on no one that his politics are inseparable from his love of hip-hop. But hip-hop’s ability to steel our nerves for a fight is not even primarily about electoral politics, but rather facing our oppressors, in the streets if necessary. I’m not sure how many Minnesotans are hip-hop heads, but their courage in resisting ICE the past couple months is the kind of bravery that hip-hop conditions you to have—the kind of bravery that our conjuncture demands.

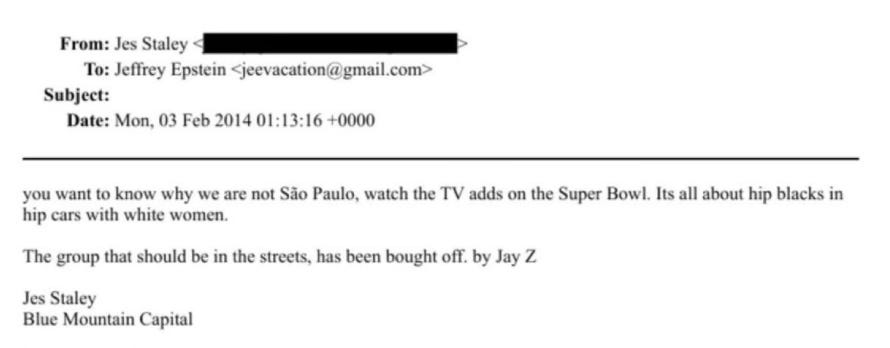

Jes Staley, the former CEO of Barclays, wrote to Jeffrey Epstein in 2014 to allay concerns he had with a populist revolt against the oligarchs, saying:

You want to know why we are not Sao Paolo, watch the TV ads on the Super Bowl. It’s all about hip blacks in hip cars with white women. The group that should be in the streets has been bought off by Jay-Z.

Even the oligarchs think we should be in the streets with pitchforks; they’re just confident we won’t bother because we’re drunk on consumption.

I watched for months last year as the Philippines was roiled by anti-corruption uprisings. The police even claimed that a group of masked men who instigated violence during a Manila-based protest in September last year:

appear to belong to a youth subculture influenced by a “hip-hop” gang and were inspired by a prominent rapper, according to the Manila Police District.

Whether the police are correct or merely scapegoating hip-hop as some twisted subconscious gesture to the Reagan era I can’t say. But what’s true is that hip-hop is the rhythm of people power in the Philippines.

Hip-hop collectives in the Philippines are focal points for social linkage, networks that are easily repurposed for political ends because resistance to oppression is built into so much of the lyrics and culture that brings collectives together. That’s why HipHop United Against Corruption (with the unfortunate acronym HUAC) formed in October last year, a hip-hop collective meant to build on the role hip-hop played in steering protest activism against government corruption in prior months.

Hey, friend! You might have noticed that I’m offering more of Un-Diplomatic without the paywall; I’m trying to keep as much as possible public. But to do that requires your help because Un-Diplomatic is entirely reader-supported. As we experiment with keeping our content paywall-free, please consider the less than $2 per week it takes to keep this critical analysis going.

Like Tupac said, “Ask Rodney, LaTasha, and many more / It’s been goin’ on for years, there’s plenty more / When they ask me, when will the violence cease? / When your troops stop shootin’ niggas down in the street.”

My pet theory is that people who don't like music don't like art in any format, because all art (other than propaganda or AI slop) expresses or represents personal freedom, rebellion, protest, and/or even revolution. In short, art is antithetical to fascism.

Great connection, Van, between music and liberation— a connection containing ambiguities, for sure. (Hitler loved Wagner, but so did Nietzsche.) I hear music (tonal complexity, varieties of vocal expression) increasingly in your prose style, which becomes more compelling as you search for ways to express your political transformation as a sign of our personal, existential growth. And for the purpose not just of nurturing your own personal enlightenment, but also of enhancing your persuasiveness. Like Emerson, writing in front of your thought, not behind it.