Public Versus Elite Intellectualism

Be Edward Said, not Larry Summers.

The ways I think about how power and the world works have changed over the past decade. A key text in seeing differently was Edward Said’s Representations of the Intellectual. It’s a trim little volume—originally a series of lectures for the BBC.

My discovery of Said, and specifically Representations, came at a pivotal period.

When I first started building a public profile on foreign policy, it was as a “defense intellectual,” speaking from a perch among the elites of the national security state.1 I was reliably cautious in my opinions—an anti-hawk, mostly—but my credibility as a public voice came primarily from my government service in the Obama administration and my association with a high-profile think tank. It didn’t hurt that I was a military veteran.

Because of what surrounded me in Washington, my understanding of what a public intellectual should be had an inside and an outside role. Inside, you were supposed to want to be a government consultant operating behind closed doors. It pays, in all the ways. Outside, you were expected to be an explainer that tried to bring the public along on government policies.

The idea was that you should do the best analysis possible—but without any real self-consciousness about having a worldview…which means not the best analysis possible—while triangulating among your career opportunities, your social networks, and what would most help policymakers do their jobs. We used our credibility to legitimate the policies of the national security state—the going concern. Did we see it that way? No, we couldn’t see that clearly because we tended to be similar in breeding (and thought).

The art of succeeding in Washington is quite literally about associating yourself with the ideas held by the well-connected and influential. And while that art may look like a grift to some, you sleep well at night if you earnestly hold the ideas you peddle.

Of course, the fact that you sleep well at night while operating this way is a major reason for so much tragedy in the world. And there’s no better avatar for what I’m describing than Larry Summers.

Summers was Clinton’s Treasury Secretary, and subsequently president of Harvard. He uses every ounce of clout he has to serve ruling-class interests at the expense of others. I’m sure there are people like him in every industry, but only in government and politics does such a person self-aggrandize by trading against the common good.

In 1991, Summers wrote a memo arguing that “underpopulated countries in Africa are vastly underpolluted” and should therefore be the site of more dumping of toxic waste. You think I’m kidding!

This is the real life version of Terry Silver’s rant from Karate Kid III.

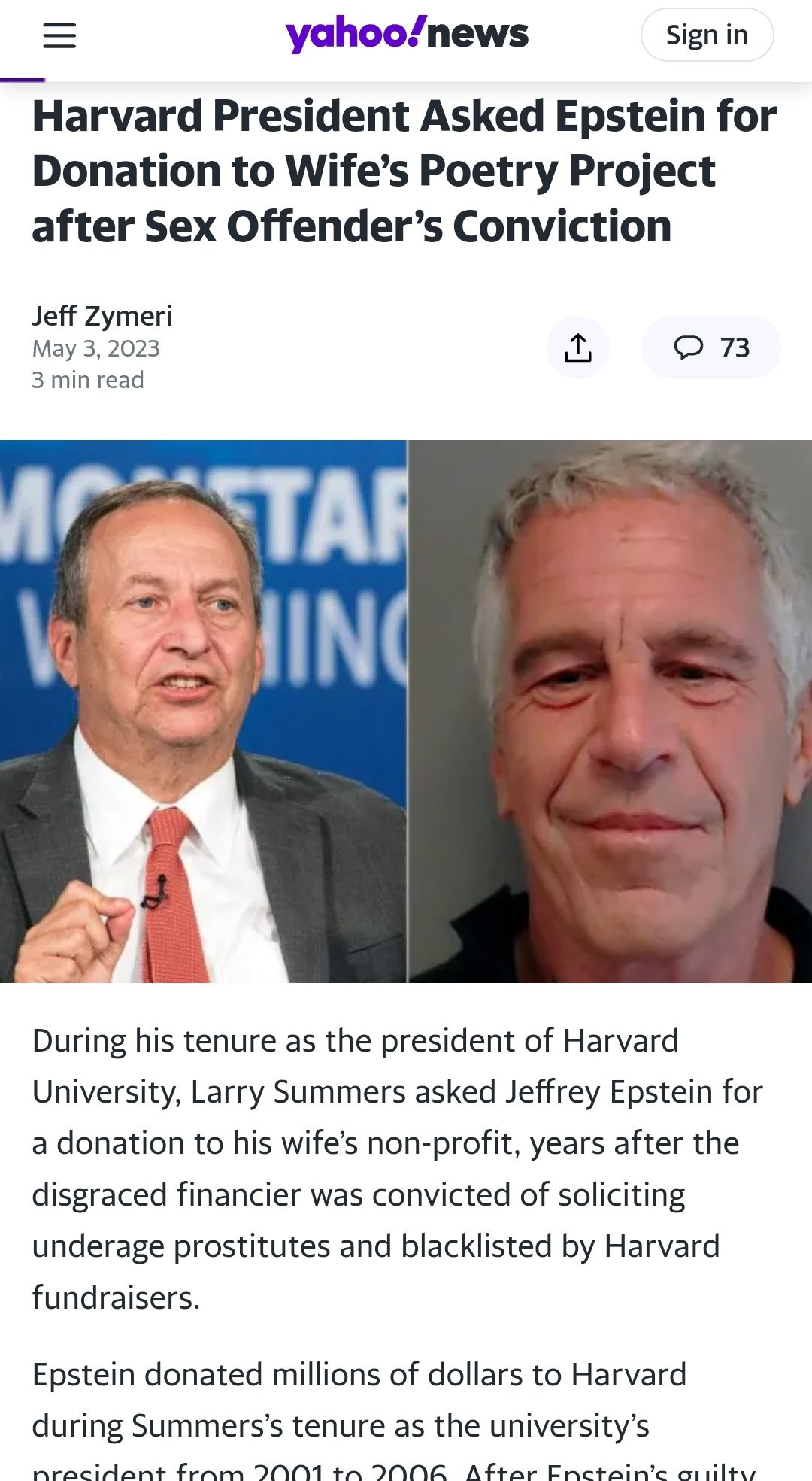

Larry Summers was also part of Jeffrey Epstein’s in-crowd, traveling with and soliciting money from the convicted pedophile and human trafficker:

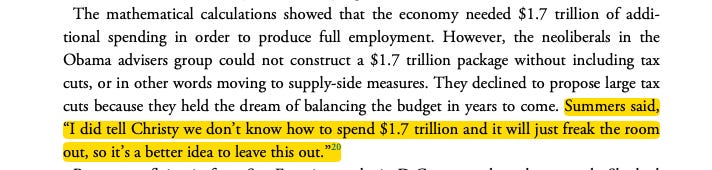

And in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008, Obama’s recovery package for the economy was a fraction of what it needed to be ($780 billion vice $1.7 trillion) not because of mysterious “politics,” but because Summers specifically intervened to advise Democrats to keep the fiscal intervention much smaller than what internal estimates suggested:

That decision, of course, led to an anemic economic recovery. I personally knew people who lost their homes in the crisis and were never helped. I personally knew people who lost their jobs, at least one of whom never recovered. Doing less than circumstances demanded heightened the dissatisfaction in the American heartland bubbling during the Obama years…and that cannot be separated from Trump coming to power in 2016.

There’s more I could say, both about Summers and people like him. But if you didn’t have an image of what a ruling-class intellectual looks like, well now you do. He exists to enrich himself at our expense, but he feels good about it (presumably) because he’s internalized what otherwise just looks incredibly cynical. He represents a milieu that sees aligning their preferences with the Galactic Empire as not just totally normal but as the only path to success.

Contra Larry Summers, the way I think about all this now is that power ought to be criticized, challenged to be more accountable, even if that means standing on your own sometimes.2 As Edward Said counseled, critically minded public intellectuals:

are always tied to and ought to remain an organic part of an ongoing experience in society: of the poor, the disadvantaged, the voiceless, the unrepresented, the powerless.

Living up to that standard means not just accepting the role of an outsider, but being an insider with the people at whose expense rulers rule.

Power is, of course, a professional aphrodisiac. Larry Summers knows this all too well. In one fascinating anecdote from Yanis Varoufakis’s door-stop of a memoir, he recounted Summers trying to school him up on the ways of Washington:

“There are two kinds of politicians.” he said: “insiders and outsiders. The outsiders prioritise their freedom to speak their version of the truth. The price of their freedom is that they are ignored by the insiders, who make the important decisions. The insiders, for their part, follow a sacrosanct rule: never turn against other insiders and never talk to outsiders about what insiders say or do. Their reward? Access to inside information and a chance, though no guarantee, of influencing powerful people and outcomes.” With that Summers arrived at his question. “So, Yanis,” he said, “which of the two are you?”

It’s hard to convey in prose what it feels like to know the sacrosanct rule of which Summers spoke—to be on the inside and play by insiders’ rules—yet go the other way. Yanis did. I did too, and have tried to write about it a couple times. But succumbing to the allure of power corrodes democracy and the tradeoff between insider and outsider is not as he presents it. Nothing is quite as Summers presents it.3

Many people in Washington would kill to have Larry Summers’s career. Fuck them God bless. But what about those of us who insist on another way? How do we know if we’re on the Summers track?

Simple: If you’re not pissing off people with power, then you might be working for them. You have to be willing to draw the ire of gatekeepers of various sorts. In a way, it’s a metric of success.

If they’re attracted to what you’re selling, check in with yourself about why. I mean, maybe the White House was looking to change some things and thought you were the smart one who said what needed to be done in just the right way. But that’s not how this stuff usually works.