Strategy & Conscience (The Book Review We Need)

In 1964, an elite scholar with friends in high places launched an eviscerating critique of national security thinking and the “strategist” profession. Here’s what he said.

One cannot play chess if one becomes aware of the pieces as living souls and of the fact that the Whites and the Blacks have more in common with each other than with the players. Suddenly one loses all interest in who will be champion. (195)

That sentence haunts me.

Before I was a scholar, I was trained as a national security strategist—to see the world as pieces on a board that I would urge to move this way but not that way. I was damn good at it. Some of the biggest names in that world once lauded me as a “rising star” and “among the best young strategists of his generation.”

That once meant a lot to me. These days, I recall their praise more as an indictment than a source of pride. I was perhaps too good at appealing to the powerful with insufficient regard for the souls attached to the pieces on the board.

I’ve never told the story of how I ended up with what others consider to be a dissident mind.1 I won’t do that here either, but one of the crucial things that had to happen for my personal evolution was to lose my religion…not only a belief in primacy and its mystification as the “liberal hegemonic order” or “rules-based international order,” but also the analytical basis for it—strategic theory.

Had I not broken out of the imaginary of the defense intellectual—had I remained seduced by the wonky, sterile, yet hyper-sexualized vocabulary of the Wizards of Armageddon—I could not have become a heterodox thinker.

I’m not sure what my old world of NatSec bros thinks happened to me, or how they process my critiques of what they say and do. For the most part, it doesn’t matter; I decided that a public intellectual should play a certain social role and that’s what I have to do regardless what they think.

But I do occasionally try to reach them with some of my arguments. It might be pointless—they have incentives to promote the expansion of the national security state, heighten the forces of nationalism, and over-rely on tools of force and coercion to “manage” global problems. But if they take seriously their own commitments to rationality, then they should be reachable with rational arguments.

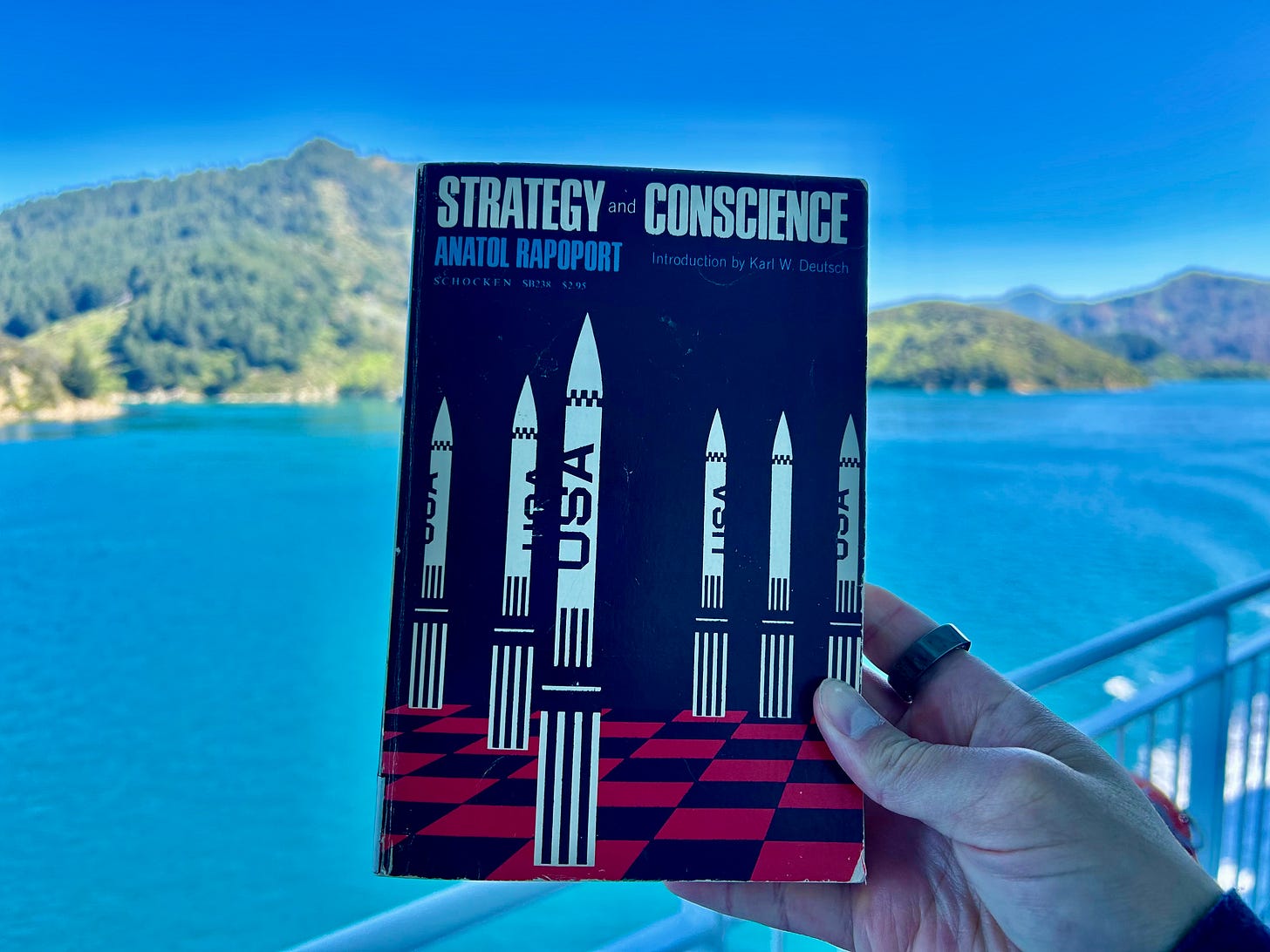

As I’ve struggled and experimented with how best to engage the typical national security wonk with critically-minded arguments that bend the world toward peace, I came across a rich, highly imperfect, but still insightful forgotten text written just after the Cuban Missile Crisis called Strategy & Conscience, by Anatol Rapoport.

The book, long since out of print and very hard to track down, has much to say to both critical analysts and national security strategists today. It tackles many themes I discuss in this newsletter, especially about the poverty of thinking like a military nerd about problems that are fundamentally political.

At the time it was written, it was an influential part of elite discourse. It carried an introduction from Harvard professor Karl Deutsch, who was a big deal in the ‘60s. And it’s cited in a number of canonical strategic studies articles.

But the book has been memory-holed by elder strategists today, while no younger strategist has likely ever heard of it (I hadn’t, except in the odd footnote). Peace scholars and critics of the national security state—to their detriment—moved away from the form of critique that Rapoport exemplifies in this book. And so there has been nobody to carry on the tradition of putting state strategy and social morality into dialogue, to take seriously—and critically tear apart—the thinking of the national security state on its own terms.

Don’t get me wrong, Strategy & Conscience has problems. It’s hardly more readable than the average political science text. I totally get why this book never caught on with the masses. But everyone—especially those who interact with the strategist vocation—would benefit from at least a familiarity with Rapoport’s arguments, which joust directly with the likes of Thomas Schelling and other Wizards.