The Green New Deal, The Far Right, and War

A review of Christian Parenti’s prescient, forgotten classic

If I’m being honest, I find most of the research on climate change to be drier than burnt toast. An extinction-level problem—a genuine crisis. Yet, until recently, the literature overwhelmingly failed to convey the pathos, urgency, or even explanatory clarity that the issue warrants.

I know I’m not alone in feeling that way.

Sure, you can dramatize the effects of environmental degradation by satirizing it, which Don’t Look Up tried to do. And you can talk about melting ice caps with doom music in the background like An Inconvenient Truth. You can even get righteously indignant and yell at the olds, like Greta Thunberg.

All of this is noble enough, and on some level serves its purpose of consciousness raising.

The problem with these efforts, as with the climate literature generally, is that they all tend to present the climate crisis as a narrative disembedded from reality.

What I mean is, we walk around with stories in our heads about the panoply of urgent, visceral political problems relating to militarized violence, unequal rights, and rich-poor divides. As Adelle Thomas recently said:

We’re relating to the climate crisis as if it’s something we’re watching instead of something we’re doing—and that mindset has enormous consequences.

Presenting climate change as a distinct or new problem without recognizing it as an organic part of our existing stories/frameworks about insecurity makes it hard for people to relate in a palpable way (and it’s all the more difficult because climate change is a structural problem whose proximate expressions can be identified as having isolated causes that do not get attributed back to the larger structure).

But the past few years, some scholars finally started to “get it.”

The new research ties climate and politics tightly together. The newer stuff doesn’t just argue “Climate change makes political problems worse”; it emphasizes the ways in which climate change is itself a political problem and its consequences follow from that.

It’s serious analysis by folks who tend to be “on the left”—historical materialists, ecosocialists, heterodox economists, and world-systems analysts. They are the group who has been way ahead of the rest of us in explaining the how and why and what now of climate intersecting with power politics and global insecurity.

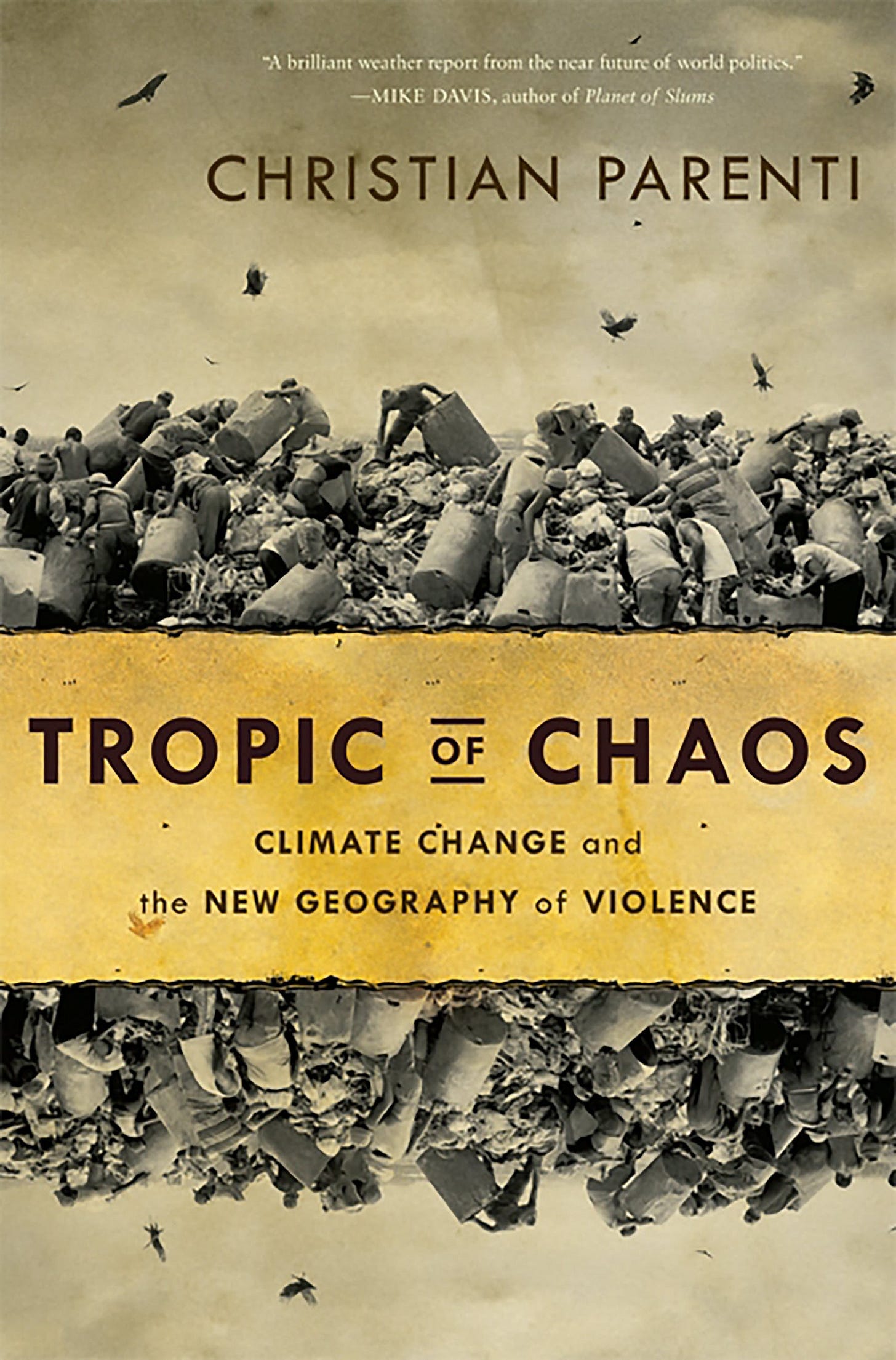

The best example of this intellectual vanguard is a stunningly good read by Christian Parenti called Tropic of Chaos: Climate Change and the New Geography of Violence.1

The book came out in 2011. Based on how publishing works, it was presumably sent to the printer in 2010, and was likely being written over 2006-2009.

I mention that because the book was UNBELIEVABLY prescient. It foretold the “polycrisis” and the rise of far-right “populism.” It also has a lot to say about how to make sense of geopolitics in our current moment.

As a book that connects the micro and the macro, and that both explains and prescribes, it’s an overlooked gem. I have to imagine the only reason it didn’t get more love from the opinion-makers is that it was published at a time when the public was not really receptive to critiques of capitalism—especially in relation to climate change.

So here’s a brief breakdown of not just what makes this book unusual, but how it anticipated today’s world situation and what it suggests about how to deal with it.