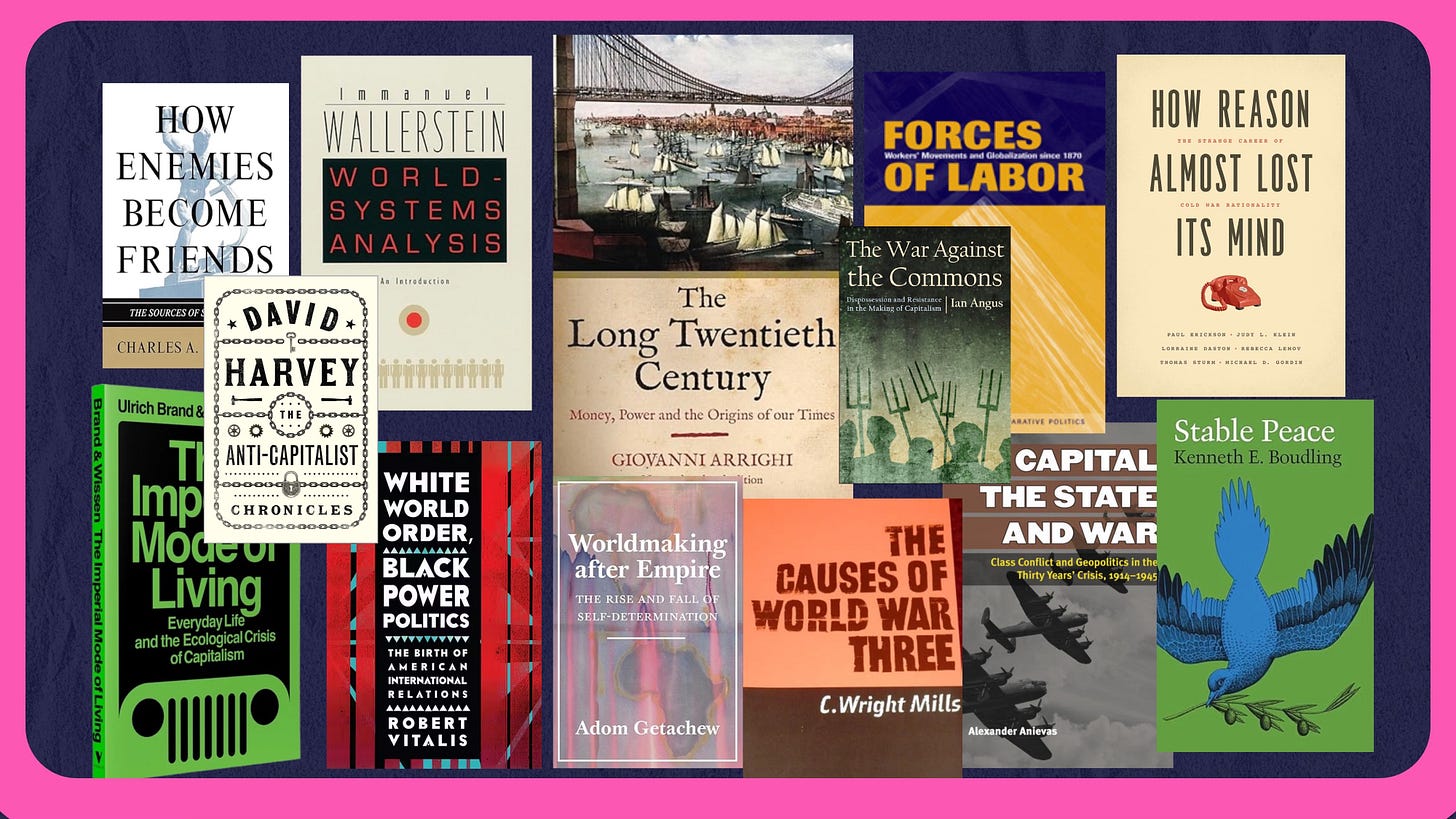

Thirteen Books for a Better International Relations Education

I’ve offered my share of criticisms about international relations (IR) as a discipline, and have given my list of some IR books to avoid. But I frequently get questions like this:

So I thought I’d suggest some books that might be core to a new canon for IR, excluding my previous two books, Grand Strategies of the Left and The Rivalry Peril, which you should obviously buy if you haven’t already!

Beverly Silver, Forces of Labor: Workers’ Movements and Globalization Since 1870

Immanuel Wallerstein, World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction

Alexander Anievas, Capital, the State, and War: Class Conflict and Geopolitics in the Thirty Years’ Crisis, 1914-1945

Kenneth Boulding, Stable Peace

Charles A. Kupchan, How Enemies Become Friends: The Sources of Stable Peace

C. Wright Mills, The Causes of World War III

Antonio Arrighi, The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power and the Origins of Our Times

Adom Getachew, Worldmaking After Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination

Robert Vitalis, White World Order, Black Power Politics: The Birth of American International Relations

Ulrich Brand and Markus Wissen, The Imperial Mode of Living: Everyday Life and the Ecological Crisis of Capitalism

Paul Erickson, Judy L. Klein, Lorraine Daston, Rebecca Lemov, Thomas Sturm, and Michael D. Gordin, How Reason Almost Lost Its Mind: The Strange Career of Cold War Rationality

Ian Angus, The War Against the Commons: Dispossession and Resistance in the Making of Capitalism

David Harvey, The Anti-Capitalist Chronicles

With the exception of maybe Boulding and Kupchan, each of these books is profoundly concerned with understanding both power politics and the historical context that shows us how power politics works. All move well beyond “the paradigm wars” that anchor much IR curricula.

The crucial virtue of these books is that each also offers a critical analysis in one of three senses: It stresses peace as a normative priority of state power; it foregrounds how power articulates itself through racial and gender exclusions; or it draws attention to class conflict as a cause or consequence of state power. Those are traditions worth retaining and building on.

Hey, there! You might have noticed that I’m offering more of Un-Diplomatic without the paywall; I’m trying to keep as much as possible public. But to do that requires your help because Un-Diplomatic is entirely reader-supported. As we experiment with keeping our content paywall-free, please consider the less than $2 per week it takes to keep this critical analysis going.

Beverly Silver, Forces of Labor: Workers’ Movements and Globalization Since 1870

I have never read a book that tried to explain the relationship between war, labor power, and labor militancy (the strike weapon). As the global capitalist mode of production changed, so have patterns of labor unrest. War, in turn, had measurable impacts on the rise and decline of labor power. This description doesn’t do justice to the arguments in the book, but it really changed the way I see international relations. And it remains one of the only books to illuminate the class blindspot in mainstream IR, using mainstream social science conventions to do so.

Immanuel Wallerstein, World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction

Wallerstein is as necessary right now as he is unfashionable. He understood international relations as a world-system defined by the capitalist mode of production. Cores, peripheries, and semi-peripheries are sites of either capital concentration or exploitation, defined by their relation to the production process. Contrary to mainstream IR theories, the world-systems lens takes what we know about the world and lets us see everything—from nationalist sentiments to international trade to great-power rivalry—from a totally different angle. An angle that has actual explanatory power. I loathe most texts that identify themselves as introductory, but this slim volume is truly an easy introduction to seeing the whole of international relations rather than just its parts.

Alexander Anievas, Capital, the State, and War: Class Conflict and Geopolitics in the Thirty Years’ Crisis, 1914-1945

Most classical insights about international relations derive from studies of World War One, World War Two, and the inter-war period. Anievas’s book, historical in a thick prose that rivals scholars like Adam Tooze, takes this same, well-trodden period in the 20th century and re-explains it with fresh, Marxian eyes. Anievas grounds his historical narrative in the concept of “Uneven and Combined Development,” originally a Trotskyist insight about the historical reality that states and other political formations (empires) have competed on unequal footing and produce a totality of relations that makes up the world-system.

In this approach, there is no “state of nature,” no ideal-type, and no single unit of analysis; only differing degrees of wealth and power giving rise to both how and with whom states combine and collide…always pushed forward toward new frontiers of capitalist exploitation by the “whip of external necessity.” The analytical device of Uneven and Combined Development is as crucial as it is underspecified. UCD works better as a concept or ontological assumption rather than a theory, but it nevertheless helps Anievas upend both realist and liberal interpretations of the 20th century.

Kenneth Boulding, Stable Peace

This little pamphlet book from 1978 critiques the balance of power and military solutionism as impediments to peacemaking. As Boulding quips, those most “prepared for war usually get it.” He posits instead a series of logical policies that are politically difficult for a country that has been at war for its entire existence—softening national borders, the GRIT method of reciprocal military restraint and confidence-building, strengthening intergovernmental institutions, proliferating peace building NGOs, and the like. Boulding, a pioneering peace intellectual, offers prescriptions that are no longer novel, but he argues for them with a coherence and force of prose rarely seen today.

Charles A. Kupchan, How Enemies Become Friends: The Sources of Stable Peace

I was reading this bulky book in 2011 when I flew up to the UN in New York to participate in bilateral nuclear negotiations with North Korea. It’s a long story, but the fact of my carrying this book turned into a brief media narrative that the AFP newswire circulated:

In a sign of the diplomatic minefield that the United States has been navigating in its dealings with North Korea, an aide accompanying Bosworth was seen carrying a copy of “How Enemies Become Friends,” a recent book by Charles Kupchan, a former adviser to president Bill Clinton, into the meeting.

I was the “aide.”

This book is a very handy crib sheet for the “paradigms” of international relations. The novelty I found in this book was not its core argument—democracies and dictatorships can be friends under certain conditions. Rather, it’s the way he links together realism, liberalism, and constructivism as each furnishing a logic of statecraft that works better or worse depending on what phase of negative versus positive peace a nation finds itself in. Policymakers like to bemoan that IR theory is useless; Kupchan begs to differ, and he does so in fairly plain language that a non-IR expert could follow.

C. Wright Mills, The Causes of World War III

Written in 1958, it predicted the Cuban Missile Crisis that came less than four years later. What Mills did not anticipate was that we would get lucky in that moment, just as we did in many other nuclear crises that could have turned out differently if not for a single decision that happened to work out favorably.

What’s special about this book—other than its unsparing prose roasting what Mills calls the “crackpot realists”—is the clarity of its analytical claims about how war happens. His mind was something of a template for my Grand Strategies of the Left in part because he distinguished proximate/immediate causes from underlying/foundational/root causes. Military buildups—the buildup, preparation, and positioning of forces for war—is the immediate cause of war in most instances; war prepping has a self-fulfilling momentum. This book is long out of print, but I discovered recently that Internet Archive has a free pdf.

Antonio Arrighi, The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power and the Origins of Our Times

Not a beach read! The prose is incredibly dense, but worth it for the ways that it clarifies many confusions in our current conjuncture. Arrighi, a scholar grounded in a world-systems perspective, engages with some of the biggest names in IR theory—Waltz, Gilpin, Keohane, and Rosenau, among others—as he goes on to introduce too many useful ideas to catalogue in a brief summary.

On one level, he’s relaying the history of capitalism as a world-system. On another level, he’s combining hegemonic stability theory with heterodox insights about the recurring crises of capital accumulation and the cyclical processes by which global order collapses and reconsolidates in new form. Along the way, he introduces many stimulating ways of thinking about the world. The most critical insight I took away from this book, which he borrowed from Braudel (1984), was that the US shift from an industrial economy to a financialized one in the 1970s signified the “Autumn” of American hegemony—a pattern of declining hegemonic order that the world has cycled through intermittently since the 14th century. Arrighi rewards the close reader, but closely reading him requires a patience that few today possess. (I’ll be writing a review of this book at some point)

Adom Getachew, Worldmaking After Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination

Getachew is a powerhouse of an intellectual, and her Worldmaking After Empire inspired how I conceived of Grand Strategies of the Left (including obviously putting “Worldmaking” in the subtitle to the book). The book’s persuasive through line has grand implications: De-colonization was a radical bid to construct a new, more egalitarian global order, not a project of “nation-building.” That de-colonization fell short can only be understood in the context of its opposition to the world’s richest and most powerful countries—specifically the US and Europe. As we try to build a post-neoliberal—or even a post-capitalist—world, we owe it to ourselves to study how intellectuals of the Third World conceived of doing much the same.

Robert Vitalis, White World Order, Black Power Politics: The Birth of American International Relations

IR is a discipline whose origins are embarrassingly racist and imperialist—anyone who thinks otherwise simply has not contended with the evidence in this book. What’s remarkable is that Vitalis published White World Order, Black Power Politics in 2015, years ahead of IR’s post-BLM turn toward racial conscientiousness and yet more original than anything to come out about the geopolitics of race since 2020. If you were trained in mainstream IR, you’ll find this book revelatory. Vitalis uncovers a “Howard school of international relations theory” meant to explain “white world supremacy from the standpoint of its victims.” It’s a damn shame that I somehow never even heard of the book until 2017, and waited close to two more years before picking it up.

Ulrich Brand and Markus Wissen, The Imperial Mode of Living: Everyday Life and the Ecological Crisis of Capitalism

This book grabbed me (and will probably grab you) from its opening pages, which used Robert Kaplan’s 1994 “The Coming Anarchy” article as its foil. I owe this book a deep read—I did a quick, shallow one a few years ago and it was enough to profoundly alter some of my ideas about national-level schemes for economic development and worker struggles. The key insight, as I’ve discussed before, is what it describes as “the imperial mode of living”:

a mode of living and production…that depends upon the worldwide exploitation of nature—and wage and non-wage labour—while simultaneously externalising the social and ecological consequences arising from it.

Thinking about “our” role (as wage workers in rich countries) in global systems of extraction, unequal exchange, and repression is a starting point for better analysis of our conjuncture. It also guards against us developing policies based on romantic understandings of either the past or our own countries’ conduct in the world. Merely having awareness of the imperial mode of living as a concept offers a way to incorporate problems of class, social reproduction, and environmental sustainability within the same analysis.

Paul Erickson, Judy L. Klein, Lorraine Daston, Rebecca Lemov, Thomas Sturm, and Michael D. Gordin, How Reason Almost Lost Its Mind: The Strange Career of Cold War Rationality

How Reason Almost Lost Its Mind works best for people already familiar with rationalist and game-theoretic approaches to IR. It takes the reader through the politics associated with “Cold War rationality,” a dangerously abstract way of thinking about war and nuclear violence that became mainstream because of its leading lights—Herman Kahn, Thomas Schelling, Bernard Brodie, and the like (all of whom are followed as characters in the book). Scholars like me came up at a time when rational choice was the only choice, and studying war like it was a de-humanized math puzzle was considered reasonable. I’m not sure I would call this a critical text, but it does an excellent job historicizing that which once seemed natural to people like me.

Ian Angus, The War Against the Commons: Dispossession and Resistance in the Making of Capitalism

Did you know Garrett Hardin—the coiner of the concept of the “Tragedy of the Commons”—was an anti-immigrant eugenist whose writing the Southern Poverty Law Center described as “frank in their racism and quasi-fascist ethnonationalism?”1 Neither did I. And that insight was the setup for The War Against the Commons. The book is a revealing history of “the enclosures” in England—the process by which the monarchy and its aristocrats privatized the commons that peasants relied on for survival, by force, leading to a number of riots and rebellions. Although focused critically on British history, its telling vivifies how capitalists social relations today are built on primitive accumulation yesterday. The refusal of anyone other than Marxists to reckon with that reality in their analysis of modern politics is why nobody other than Marxists anticipate America’s turn toward an imperialist foreign policy.

David Harvey, The Anti-Capitalist Chronicles

Speaking of Marx, I’m only just now reading this book, and not quite finished, but have so far found it breathtakingly clear in its prose, its worldview, and its analytical claims. If you’re Marx-curious, this is an approachable entry point. It offers a radical rethink of not just capitalism as a mode of production or source of social ordering, but a different way of understanding our ongoing crisis of capital accumulation, which finds expression in fascist politics, AI bubbles, and inter-imperialist jingoism.

Hello, friend! You might have noticed that I’m offering more of Un-Diplomatic without the paywall; I’m trying to keep as much as possible public. But to do that requires your help because Un-Diplomatic is entirely reader-supported. As we experiment with keeping our content paywall-free, please consider the less than $2 per week it takes to keep this critical analysis going.

I still teach the tragedy of the commons as a concept, but with a healthy dose of context and caveating.