Working-Class Interests in Progressive Foreign Policy

AOC’s forthcoming remarks at the Munich Security Conference are said to center the working class, which is a much-needed departure from US foreign policy as it’s actually existed my entire life. It’s also to be expected. As my co-host Matt Duss told NBC News:

Matt Duss, who is advising Ocasio-Cortez on foreign policy, told NBC News that she was invited to…give her prognosis of right-wing populism and provide a “working class perspective” on the intersection of domestic and foreign policy, as Duss put it.

“Her approach to global affairs is very deeply connected to her approach to domestic affairs — based on the same principles,” Duss said. “She believes in diplomacy as a tool of first resort. She’s supported reining in the executive branch when it comes to war. She believes the U.S. has an important role to play around the world, but military intervention is not the way to do that. And there’s clearly a strong constituency in the country that agrees with that. That’s a constituency Trump and [Vice President JD] Vance appealed to.”

In anticipation of her remarks, I’m re-issuing a piece I originally wrote in 2023 about foreign policy in relation to the working class and progressive politics. I can think of no reading that would better prepare you for what’s she’s about to say.

Hey, friend! You might have noticed that I’m offering more of Un-Diplomatic without the paywall; I’m trying to keep as much as possible public. But to do that requires your help because Un-Diplomatic is entirely reader-supported. As we experiment with keeping our content paywall-free, please consider the less than $2 per week it takes to keep this critical analysis going.

A properly progressive foreign policy1 is a working-class foreign policy. The complication is that working-class demands on foreign policy are capable of breaking in radically different political directions.

Let me back up a second.

When I think about international relations, and especially when I critique US foreign policy, my perspective is oriented toward the material interests of the working classes.

But when I was writing Grand Strategies of the Left—a project that maps out different models of root-cause thinking about how the state should relate to the world—I ran into a troubling realization. The class position of those advocating for worker interests were inescapably bourgeois, even elite. Chris Rock’s joke hit a little close to home:

I’m rich. But I identify as poor. My pronoun is “broke.”

I kid. But seriously, missing in action from the public conversation about foreign policy while I was writing that book were the voices of organizations whose members actually were working class—specifically labor unions. They were part of politics during the Trump years, but they just weren’t pushing many foreign-policy demands at the time. Specifically, they were not offering positions on the list of issues that policymakers obsess about.2

And this is why I love one of the more recent trends captured in a short, punchy piece in The Nation by my friend Spencer Ackerman.

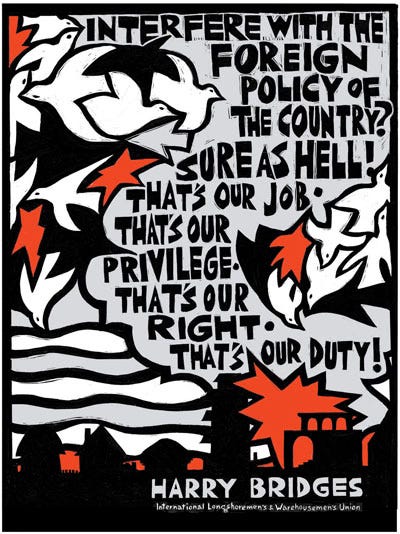

His column this week, “A Working-Class Foreign Policy is Coming,” foregrounds working-class voices speaking directly about foreign policy interests via their unions.

As Spencer tracks in his piece (and as Alex Press has tracked for a while), dozens of unions—including the mighty UAW—signed onto a statement demanding an immediate ceasefire and an end to Israel’s terror campaign in Gaza. That’s the same position that progressive, social democratic, and antiwar voices have advocated from the start.

And whereas the UAW is actively investigating how to rekindle the peace-conversion projects from the ‘90s and divest from the military-industrial complex generally:

few in respectable foreign-policy circles consider the size of the US defense industry a problem to be solved. That’s a measure of how underrepresented the working class is in US foreign policy.

I’ve said this many times in many settings, but the thing that alienated me from the Washington Establishment was precisely its cold shoulder toward the working classes. In the preface to my damn book, I even bemoan:

why is the plight of workers—average Americans—totally absent from the geopolitical machinations of the national security state?

Your Government’s Foreign Policy Doesn’t Care About You

Washington’s default grand strategy of primacy is strategically unsound on its own terms. But as a grim practical reality too, a foreign policy that insists on reliving the Cold War makes working people cannon fodder. And to whose benefit? Oligarchs and flag-waving reactionaries. Or, as Spencer quotes a UAW member:

You get there and you realize, oh, these people are poor as shit…You got a poor shithead from Philly fighting a poor shithead from fucking, I don’t know, Najaf or somewhere [else] in Iraq. It’s an endless cycle of people who don’t have shit being forced to fight people who don’t have shit.

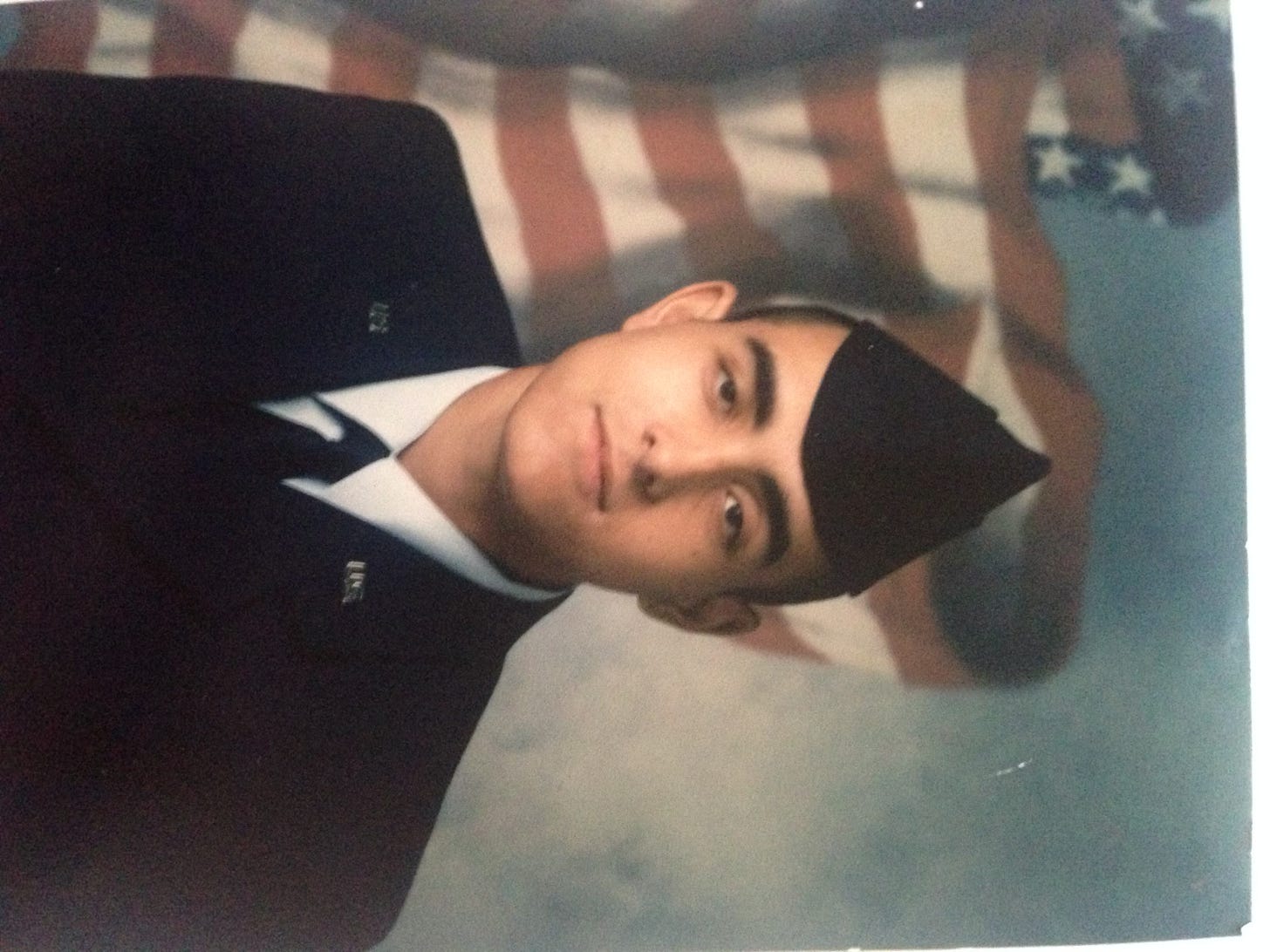

That’s what it felt like when I was enlisted in the military. You want to do what’s in the common good, and you have a naïve sense that signing up and following orders is the way to do it.

But then you get in the system and find that nobody’s actively thinking about the common good. Your buddies are getting PTSD and committing suicide for depraved abstractions. “National interests” become what well-heeled elites decide they are, usually in self-dealing backrooms and think tank panels. And the real-world operations that you carry out end up targeting poor bastards who might’ve been you if you were born under different circumstances.

The worker-forsaking nature of US foreign policy (most countries’ foreign policies) reflects a class blind spot that owes partly to drawing policymakers overwhelmingly from the Ivy League.

As long as I didn’t think too hard about where I came from, being in the mix with America’s aristocratic class felt really good—jetsetting, cocktails, good food, great money, invitations to White House galas. If you saw my recent Fiji dispatches, you know I’m a sucker for that bourgie shit. What’s not to love?

Well, the higher up you go as a DC insider, the more you become the mouthpiece for policies that fly in the face of the common good.

You have to police respectable opinion as you determine guest lists, identify panel speakers, and collaborate on research grants.

You find yourself in the position of explaining to journalists and young interns why, if they only knew what you knew, they too would conflate the power of the national security state with the common good.

And then you talk to your working-class friends that you grew up with, or served in the military with, or train on the jiu jitsu mats with, and find that you speak a language that makes no sense to them at all. You can’t help but wonder—whose side are you on?

Perhaps I’m projecting from my own experience a bit. But the point is, if you work in foreign policy and any part of you remains idealistic or thinks we owe something to our fellow humans, eventually the contradictions become too much to bear.

Separating the Real from the Fake

But the reason I say progressive foreign policy is working-class foreign policy is this: A properly progressive worldview is committed to antimilitarism and recognizes that there is no “security” in this world without greater peace, democracy, and equality. Those commitments follow from taking seriously how real people are impacted by what we do with foreign policy. That is why the labor position on Gaza and Israel is the same as the left position.

But it’s also the case that workers are not a unified mass, do not share a collective consciousness (for now), and are not “woke” in the tokenistic sense. As Spencer notes in his piece:

close to 40 percent of the autoworker membership voted for Trump in 2016.

The working class occupies an objective class position in relation to capital, and that binds their fates (our fates) together…but that objective position does not necessarily determine objective calculations of interest. Nicolas Delalande said it perfectly, writing of the International Workingmen’s Association of the 19th century:

the objective conditions of the economic process created a solidarity of position, but this did not imply the existence of solidarities of demand and action.

For instance, unless your economy is wholly autarkic, economic nationalism is objectively bad for the world’s working classes…and yet, that kind of agenda can appeal to people’s sense of desperation or fear. People can be put into a zero-sum mindset that leads them to conclude their interests lay in exclusion rather than solidarity. Labor unions were the original internationalists, and only turned protectionist under the immiserating pressures of neoliberalism.

What I’m saying is we can’t take for granted that labor = left. It therefore follows that the UAW and other unions could stake out positions in some alternative future that are highly reactionary or protectionist.

But any set of foreign policies that prioritizes workers as a whole has to be antimilitarist; has to be committed to peace, democracy, and equality.

Why?

Because, by definition, workers as a whole don’t benefit from some being haves and some being have-nots. They don’t benefit from lacking political power. And they sure as shit don’t benefit from being overrepresented in the casualty counts for avoidable wars.

Properly is doing a lot of work in “properly progressive foreign policy.” But I’m aware of at least two versions of fake-progressive foreign policy that make me inclined to avoid the term progressive altogether. Alas, I’ve chosen to fight for it instead. More on this another day.

The Working Families Party does take thoughtful positions on foreign policy and its members are overwhelmingly…working families. But a) they’re the exception to the rule, and b) even they had not articulated a comprehensive foreign policy agenda during the Trump years. Worker-aligned policy advocacy has a problematic history of being reactive, ad hoc, and issue-based.